[ad_1]

Chris Andrews and Catherine Morrison,BBC News NI

BBC

BBCThe events of D-Day and the spirit of the war effort are best told by those who lived through it.

With each passing year such first-hand accounts become more precious to record as photographs, mementos and stories are passed on for future generations.

To mark the upcoming 80th anniversary of the Normandy landings, BBC News NI has spoken to two veterans with different experiences to share, at home and overseas.

George Horner is one of the last surviving Royal Ulster Rifles veterans from D-Day.

Ada Chell followed events from a barracks in County Antrim and lost someone special to her.

A 24-hour job at wartime

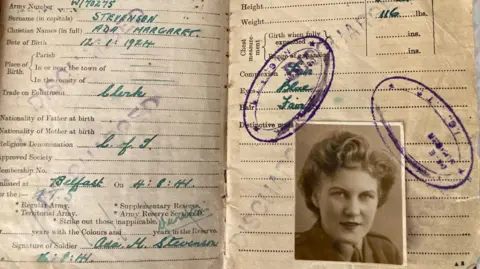

Ada, from Bangor, joined the women’s branch of the Army, the Auxiliary Territorial Service, when she was 17 in 1941.

Three years later she followed the events of D-Day from Thiepval Barracks in Lisburn.

Now 100, she remembers the scenes of celebration when news of the Normandy landings began to filter back.

The war was a busy time for young Ada.

“I seldom got out because it was, I would say, a 24-hour job,” she told BBC News NI.

“In the front office we had a brigadier and his assistant. Then in the back office was a sergeant major and then the big map on the wall.

“I was in charge of the dispatch riders for all of Northern Ireland.

“At that time to get a cup of petrol was difficult. And the dispatch riders had to go to all the barracks. I was in charge of them and it was trying to not send them on a long journey, but to try and break up that journey.

“It saved a lot of petrol.”

This was essential work as the riders were bringing important messages from London.

Not only was petrol hard to get, but food was becoming increasingly scarce.

But despite the Belfast Blitz, and nearly five years of war, Ada said people’s resolve had not faltered by June 1944.

‘Oh jubilation, that it was over’

“It was difficult, you had to queue for food and things like that, everything was rationed, even coal, you couldn’t get coal to heat your fires,” she recalled.

“I think it was more worrying that they were going to get a notification [of a death or serious injury]. But then all the news that was coming through about what was going on in Germany and finding out about these [concentration] camps.

“And seeing these people, the cruelty that had gone on, that was something that the young today have no idea about, the horror.”

On D-Day itself, she remembered the sense that “something big” was happening.

“They had something going on that day – like a celebration. That’s what I can remember. I worked in the pay office. Oh jubilation, that it was over, at least they thought it was over.

“Oh yes, something big was happening and there was joy, yes, at that moment.”

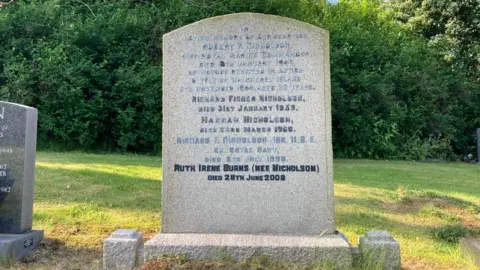

With the joy, however, came a personal loss – a young suitor of Ada’s, Robert Nicholson, a Royal Marine, died of his injuries.

“You know what it’s like when you’re young, and you meet someone you like and they like you, and you got a peck on the cheek and that’s all you got,” she said.

“We were very old fashioned in those days.

“On D-Day, the day of the invasion, he was in the Royal Marines, and I got a letter from him saying he was going to be moved.

“Then I got a card from him, I saw him briefly for an hour and then he was called back again.

“He got shrapnel in his lungs, he was a commando.”

Robert Nicholson died in January 1945 of wounds inflicted in the Netherlands.

Less than a year later, victory was declared in Europe.

“It was unbelievable, but it was sad,” Ada explained.

“I had lost so many friends. Some came home but some didn’t. There was joy and there was sadness.”

And still to this day Ada remembers her friend Nicky, as she calls him.

“I went to a British legion concert. They asked me to make a speech. I couldn’t speak, the only thing I could see was Nicky’s – all I could see was his gravestone. He was only 21.”

What is D-Day?

D-Day, also known as the Normandy landings, was one of the most significant events in World War Two.

Tens of thousands of Allied troops landed in gliders and on the beaches of northern France on 6 June 1944.

It was the largest seaborne invasion in history and marked a turning point in the fight against Nazi Germany.

‘I did what I had to do on D-Day’

George Horner, from Carrickfergus in County Antrim, was a sergeant with 2nd Battalion Royal Ulster Rifles (RUR) on D-Day, landing at Sword beach.

The 97-year-old said his father had served in the 36th Ulster Division during World War One and offered him one piece of advice: “Keep the head down and get behind somebody taller than you.”

George said he ignored the paths of his brothers in the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force as he “wasn’t a great swimmer” and he “didn’t like flying in case the plane crashed”.

After starting his Army career in Omagh, County Tyrone, he moved to England and worked for a time as a Morse code signaller.

However, D-Day is etched in George’s memory.

“6 June 1944 – I remember it well,” he said.

The 2nd Battalion began landing at the Queen Red Beach area of Sword from midday.

Their objective was to move quickly inland and prepare to fight for the city of Caen.

During a “rough crossing” over the English Channel, George remembered saying to himself: “Horner you got in here with the two legs and two arms, that’s the way we have to come out.”

Horner family

Horner familyLeaving the landing craft ashore, he described having to wade in and avoid metal obstacles which made the beach approach “rough in places”.

“There’s a brave few boys lost their lives there,” he said.

Later in the war, the veteran said he remembered coming under attack from members of the Hitler Youth in Germany.

“I remember going through this wee village and we were headed up and there was heavy fire coming from a corner shot, you know, and I had a bazooka,” he said.

“That’s for taking out tanks, knocking down buildings, and I couldn’t get close enough to make it effective, so I called up for tank support.

“Three kids, they were doing all the trouble, two wee girls and a wee lad. They couldn’t have been anymore than about 13, 14.

“They belonged to an organisation which I found out later was the Hitler Youth group, but that didn’t make it any easier for me.

“It was the only time I cried. You’d no choice.”

MoD

MoD‘People you could depend on’

On his comrades, he remembers having some very good friends and “people you could depend on”.

One of them, a Lisburn soldier who was killed in action, lent money to George. He had told him: “The next time I see you I’ll give you it.”

Michael Cooper

Michael CooperThe RUR soldier has fond memories of seeing Winston Churchill during a victory parade in London.

“I could have touched Churchill as he was walking past,” he reminisced.

George went on to serve as president of the Carrickfergus branch of the Royal British Legion.

In March 2024, he was a special guest at the Royal Irish Regiment’s St Patrick’s Day parade in Lisburn with his daughters.

He was presented with the first shamrock by the Duchess of Edinburgh.

Asked if he regards himself as a hero for his service, George said “no” and that he “takes it as it comes”.

“I did what I had to do. Nothing special.”

[ad_2]

Source link freeslots dinogame telegram营销