[ad_1]

By Craig Williams and Chris Diamond, BBC Scotland News

Getty Images

Getty ImagesGeorge Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four was published 75 years ago on Saturday.

It is the story of Winston Smith, an obedient citizen in an oppressive future state who slowly rebels against the system.

The book is a powerful study of totalitarianism and its effect on the individual.

It takes place in a future world of war, poverty, rationing and absolute state control.

Every action, word and even thought is monitored and controlled by the leader, ‘Big Brother’, and ‘The Party’.

It was written in a world ripped apart by fascism and against the backdrop of the early days of the Cold War and the spread of communism.

The novel is set in a London re-imagined as ‘Airstrip One’, the capital of ‘Oceania’. It is a rainy, filthy city, crumbling and battered, and almost entirely devoid of colour, warmth or comfort.

But it was written in an isolated and beautiful corner of the Isle of Jura as the author, afflicted by the tuberculosis which would soon kill him, sought to escape the noise, smog and damp of London, and get his warning to the world completed before he ran out of time.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesRichard Blair turned 80 in May. A retired businessman, he has spent the past few decades minding the legacy of his father, Eric Arthur Blair – known to readers the world over as George Orwell.

Richard was adopted by Orwell and his first wife Eileen O’Shaughnessy just weeks after he was born in 1944.

His new mother died little less than a year later, leaving father and infant son alone together.

In the years following the end of the war in 1945, Orwell – finally well-off from the success of his novel Animal Farm after years of poverty – looked after Richard with the help of his family and a housekeeper.

But after a visit to Jura in September 1945, he began planning to move there.

He returned to the island repeatedly over the coming two years, bringing with him his extended family including his sister Avril and her partner.

He finally fulfilled his wish to decamp to the island full time in April 1947.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe house they rented, Barnhill, sits in the north of the island. It was barely habitable. Shabby, damp, cold and alone at the end of more than four miles of single track path.

Yet Richard has nothing but happy memories of his time there. His father was pleased with the move, too.

“It was a nice house. A bit rough and ready, but for him it was a lovely place to go to. Remote, certainly. It was, as he described it to friends, a ‘most un-get-at-able place,'” he says.

Richard credits his aunt with making the place habitable.

“Without her it would have been very difficult for my father to have survived properly. She was very practical and a good home-maker. So she got the house comfortable. As warm as one could expect it to be made.”

Alamy

AlamyMuch has been made of the often harsh Hebridean climate and whether Jura was the best place for a man suffering from tuberculosis.

It has even been suggested that living there in such spartan circumstances may have contributed to the grim tone of Nineteen Eighty-Four.

Journalist Alex Massie, who is a regular visitor to the island, is sceptical.

“Orwell’s decision to live in the Hebrides – a long, long way away from London at a time when he was suffering from poor health – has created this vision of the sort of doomed novelist writing himself to death at the end of the world,” he says.

“That is a very romantic vision obviously, but it’s not one that bears very much scrutiny. In certain respects Jura was a healthier place to live than London. And so it was not some sort of mad or suicidal sojourn.

“It happened to be Jura that he went to, but almost anywhere that was isolated and rural would have sufficed because what he wanted was peace.”

Alamy

AlamyThat certainly corresponds with Richard’s memories.

“I loved it. It’s a wonderful island and for a kid it was just total freedom. Unlike London, on Jura you could just open the back door and off you went. There were thousands of acres of land you could walk over,” he says.

While the young Richard was enjoying the scenery and freedom, his writer father was avoiding the typewriter by working the land.

“He had by this time managed to try to get the garden dug over and planted. So that gave him a break from writing Nineteen Eighty-Four, which he had just started.

“Once he had established the garden, so he was growing vegetables, that was obviously of paramount importance for food. Because obviously it was the days of rationing and getting food was really difficult.

“We actually had a very good lifestyle. We had access to fish, to lobsters, to crabs. We had access to meat in the form of rabbits and lumps of venison that came from the estate from time to time.

“From that point of view we lived extremely well, if simply,” he says.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesOrwell continued writing, though his health was deteriorating. At the end of 1947 he was hospitalised at the sanatorium in Hairmyres Hospital, then in the countryside outside Glasgow, but now in the new town East Kilbride.

When he returned to Jura in the summer of 1948 he was only just well enough to work on the book for which he would become most celebrated.

He completed it just before Christmas and the Blair clan left Barnhill for the final time in January 1949. Nineteen Eighty-Four was published five months later.

The following January, Orwell died after an artery burst in his lungs. He was 46.

Getty Images

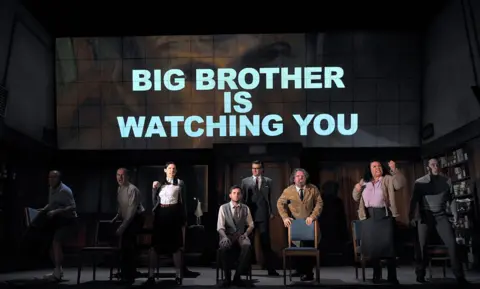

Getty ImagesNineteen Eighty-Four is a book whose reputation has grown and grown. Controversial from the moment it was published, it was unpopular with many on the left who were unhappy with what they saw as an attack on communism.

But it sold and kept selling. An acclaimed BBC production in 1954 brought it to a wider audience, and it gradually made its way onto college and school courses around the world.

It has now sold more than 8 million copies, been adapted many times for stage and screen, and, in what can be seen as the ultimate measure of its power, was banned in the Soviet Union until 1988.

But as the book reaches its 75th anniversary, its greatest influence may be in how it changed the way we speak and think. In that way, it has come to mirror the very themes the book explores.

“Big Brother”, “Groupthink”, “Thought Police”, “Thought Crime”, “Room 101”, even the description “Orwellian”.

The book has left us with a rich legacy of words and ideas to describe the power of the state, totalitarianism, the role of technology and what it is to live in a surveillance culture.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesFor writer and film critic Hannah McGill, much of its power comes from its predictions.

“Sometimes I do think you get a sort of miracle of prescience with a certain piece of work, where it happens to hone in on a few ideas that prove to just really predict the preoccupations of the coming age,” she says.

“One thing that the book predicted correctly is that we now live in a society far, far more dominated by technology in ways that Orwell could not imagine, because nobody could.

“You only have to look at the role of the telescreen in Nineteen Eighty-Four and the fact that you now have this medium which is entertainment, propaganda, advertising and surveillance all at the same time.”

For Alex Massie, the book’s influence goes way beyond its success as an imaginative work.

He says: “It’s a book that many people think they know a lot about even if they haven’t actually read it and that’s quite unusual.

“And what makes Nineteen Eighty-Four quite distinct and a monumental achievement in certain ways is that you can have strong views about it without having read it.”

For Richard, his father’s greatest work remains prescient for the warnings it gives us about the world we continue to live in. For him, it remains relevant in the age of spin and modern technology.

“Any sort of situation where you are being fed disinformation, which can come from either left or right, which can come from whatever organisation wants to put it out there.

“They want to guide you down the path they want to take you. And I would suggest that is what has become ‘Orwellian'”.

You can hear Richard Blair talking about Nineteen Eighty-Four and Jura on the weekend edition of Good Morning Scotland on Radio Scotland from 08:00 on Saturday 8 June and afterwards on BBC Sounds.

[ad_2]

Source link freeslots dinogame telegram营销