[ad_1]

By Abdelrahman Abu Taleb, BBC News Arabic

Reuters

ReutersIran and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) have been accused of violating a UN arms embargo by supplying drones to the warring sides in the 14-month conflict that has devastated Sudan. We look at the evidence to back up the claim.

On the morning of 12 March 2024, Sudanese government soldiers were celebrating an unprecedented military advance. They had finally recaptured the state broadcaster’s headquarters in the capital, Khartoum.

Like most of the city, the building had fallen into the hands of the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) at the start of the civil war 11 months earlier.

What was notable about this military victory for the army was that videos showed the attack was carried out with the help of Iranian-made drones.

In the early stages of the war, the army relied on the air force, according to Suliman Baldo, director of the Sudan Transparency and Policy Observatory.

“The armed forces found all their preferential forces besieged, and they had no fighting forces on the ground,” he says.

The RSF maintained ground control of most of Khartoum and Darfur in the west of Sudan, while the army maintained its presence in the sky.

By early January 2024, a video emerged on Twitter of an army drone shot down by the RSF.

According to Wim Zwijnenburg, a drone expert and head of the Humanitarian Disarmament Project at Dutch peace organisation PAX, its wreckage, engine, and tail resembled an Iranian-manufactured drone called Mohajer-6.

The Mohajer-6 is 6.5m long, can fly up to 2,000 km (1,240 miles) and carry out airstrikes with guided freefall munitions.

Planet Labs

Planet LabsMr Zwijnenburg identified another version of the drone in a satellite image of the army’s Wadi Seidna military base, north of Khartoum, taken three days later.

“These drones are very effective because they can identify targets accurately with minimal training,” he says.

Three weeks after the Mohajer-6 was shot down, a video emerged of another drone downed by the RSF.

Mr Zwijnenburg matched this one to the Zajil-3 – a locally manufactured version of the Iranian Ababil-3 drone.

The Zajil-3 drones have been used in Sudan for years. But January was the first time they were employed in this war, as observed by the BBC and PAX.

In March, Mr Zwijnenburg identified one more version of the Zajil-3 captured in a satellite image of Wadi Seidna.

“[It is] an indication of active Iranian support for the Sudanese army,” he says, although Sudan’s governing council has denied acquiring weapons from Iran.

“If these drones are equipped with guided munitions, it means they were supplied by Iran because those munitions are not produced in Sudan,” Mr Zwijnenburg adds.

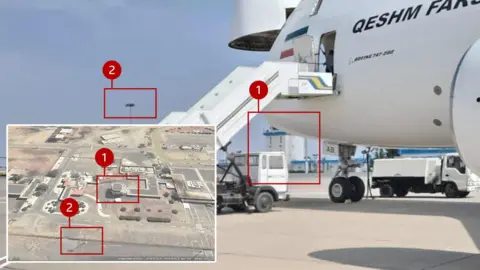

In early December, a Boeing 747 passenger plane belonging to Iranian cargo carrier Qeshm Fars Air took off from Bandar Abbas airport in Iran, heading towards the Red Sea before disappearing from radar.

Hours later, satellites captured an image of a plane of the same type at Port Sudan airport in the east of the country, where Sudanese army officials are based.

A photo of the same plane on the runway later circulated on Twitter.

X @SudanSena

X @SudanSenaThis flight was repeated five times until the end of January, the same month the use of Iranian drones was documented.

Qeshm Fars Air faces US sanctions due to numerous accusations of transporting weapons and fighters around the Middle East, particularly to Syria, one of Iran’s main allies.

Sudan had a long history of military cooperation with Iran before relations ended in 2016 due to a conflict between Saudi Arabia and Iran, with Sudan siding with Saudi Arabia.

“Many Sudanese weapons were locally made versions of Iranian models,” says Mr Baldo from the Sudan Transparency and Policy Observatory.

Since the start of the current conflict, the Sudanese government has restored relations with Tehran.

According to Mr Baldo, each side has its objectives.

“Iran is looking for a foothold in the region. If they find geostrategic concessions, they will certainly provide more advanced and numerous drones,” he says.

The BBC contacted the Sudanese army, Iran’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Qeshm Fars Air to comment on the allegations that Iranian drones are being used in the conflict but has not had a response.

But in an interview with the BBC, Malik Agar, vice-president of Sudan’s Sovereign Council, said: “We do not receive any weapons from any party. Weapons are available on the black market, and the black market is now grey.”

@RapidSupportSdn

@RapidSupportSdnMeanwhile, evidence emerged early in the war that the RSF has used quadcopter drones made from commercial components, capable of dropping 120mm mortar shells.

Images and footage on social media show the army had shot down many of these drones.

Brian Castner, a weapons expert at Amnesty International, points the finger at the UAE.

“The UAE has supplied its allies with the same drones in other conflict areas such as Ethiopia and Yemen,” he says.

X @war_noir

X @war_noirAccording to a UN report presented to the Security Council earlier this year, aviation-tracking experts observed a civilian aircraft air bridge allegedly transporting weapons from the UAE to the RSF – an allegation the UAE denies.

The route starts from Abu Dhabi airport, passes through Nairobi and Kampala airports, before ending at Amdjarass airport in Chad, a few kilometres from Sudan’s western border, and Darfur, where the RSF has its stronghold.

The UN report also cites local sources and military groups reporting that vehicles carrying arms unload planes at Amdjarass airport several times a week, before travelling to Darfur and the rest of Sudan.

“The UAE also has economic interests in Sudan and is seeking a foothold on the Red Sea,” says Mr Baldo.

The UAE has repeatedly denied these flights have transported weapons, saying they were delivering humanitarian aid instead. In a statement, a government official tells the BBC the UAE is committed to seeking “a peaceful solution to the ongoing conflict”.

The RSF has not responded to the BBC’s request for comment.

The drones that both sides in the civil war have allegedly imported violate a UN Security Council resolution issued in 2005, which prohibits the supply of weapons to the Sudanese government and armed factions in Darfur.

“The Security Council must take responsibility and consider the state of Sudan, the approaching famine, and the number of people killed and displaced, and immediately enforce a comprehensive arms embargo on all of Sudan,” says Mr Castner.

Since the appearance of drones in Sudan’s skies, the situation on the ground has partially changed.

The Sudanese army has managed to break the siege imposed on its soldiers in several locations.

And the RSF has withdrawn from some neighbourhoods west of the capital.

According to Mr Baldo, this change has happened thanks to the Iranian drones.

After more than a year of war, at least 16,650 civilians have been killed, according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (Acled).

The UN’s International Organization for Migration (IOM) estimates 12 million people have been forced from their homes – more than in any other current conflict.

Abdullah Makkawi is one who has now fled to Egypt. When he was still in southern Khartoum last July, he says he narrowly escaped death when drones, which he says belonged to the RSF, attacked.

“I rushed into the house, and we took refuge in a room with a concrete roof… My mother, four siblings and I hid under the beds,” he says.

Mr Makkawi says they heard the sound of a drone shell falling onto the next room, which had a wooden roof.

“If we had been in the other room, we would all have been killed. We survived by a miracle,” he says.

At the beginning of 2024, the conflict spread to new areas outside the capital. Civilian deaths due to drone attacks were reported for the first time in northern, eastern and central Sudan.

Before fleeing to Egypt, Mr Makkawi left his family in Port Sudan, considering it a safe place. But now he fears drones might reach them there too.

“Sudanese people are tired of the war. All we want is for the war to stop. If foreign countries stop supporting both sides with weapons, it will end.”

More about Sudan’s civil war from the BBC:

Getty Images/BBC

Getty Images/BBC[ad_2]

Source link