[ad_1]

By Marianna Spring, Disinformation and social media correspondent

BBC

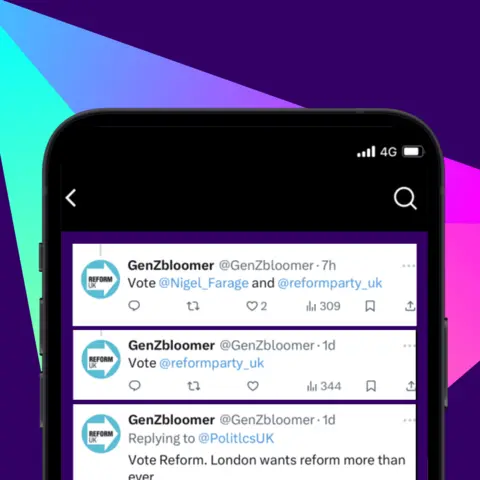

BBC“Vote Reform UK”, “Only Reform UK has a real plan for Britain” – an account on X has posted these and similar messages every couple of hours since the start of the election campaign.

The account, GenZBloomer, is one of dozens across X, Instagram, Facebook and TikTok which the BBC has identified as posting hundreds of repeated messages in comment threads expressing support for Reform UK.

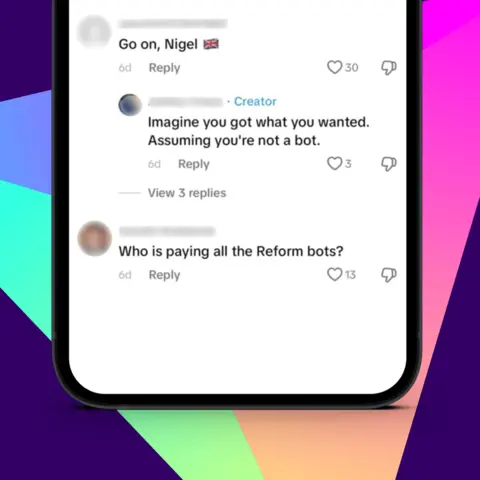

Their behaviour has prompted claims from other social media users that they are fake – automated “bot” accounts – and they are distorting the online conversation to try to exaggerate the popularity of Reform UK.

The BBC contacted people behind the accounts and found that some are genuine UK voters who believe they are helping the party through their own initiative. Others, however, failed to prove they were authentic.

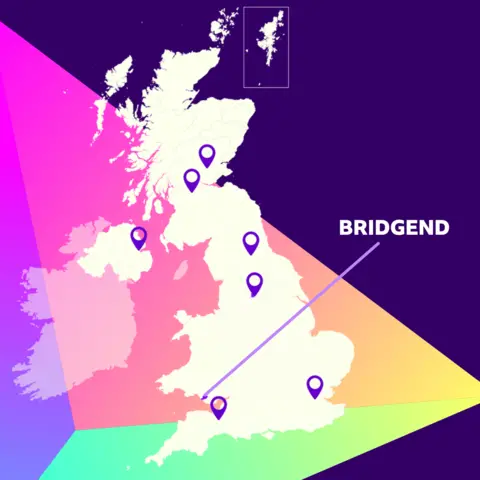

I spotted this pattern of comments in posts recommended to the feeds of our Undercover Voters – 24 fictional people based around the UK with social media accounts, created to investigate what content is recommended to different types of voters during the election. The profiles are private, with no friends. They just like, follow and watch relevant content.

“The main purpose of my account at this time is to restore British culture and values,” the GenZbloomer account told me in a message.

Following concerns about foreign interference in previous elections, some social media users have suggested that GenZbloomer – and other similar accounts – may not be based in the UK. They have pointed out phrases a native speaker would be unlikely to use, such as “make an article” instead of “write an article” and “neighbourhood tavern” instead of “local pub”.

Others are convinced the GenZbloomer profile must be parody – particularly referring to a blog post the account shared on X about how “young men are struggling out here to find traditional British women to date” because women think they are “better than everyone else because of Love Island and Starmer”, referring to the Labour leader Sir Keir.

The person who claimed to be behind GenZbloomer told me they were based in “the Annesley England area” – an unusual way to describe the small village in Nottinghamshire – and gave me a UK mobile phone number.

They agreed to speak to me on the phone, but then did not answer any of my calls.

On WhatsApp, their account is labelled as a business account for a “consulting agency”, and features a profile image of a faceless cartoon figure with a microphone headset on.

In messages with grammatical mistakes, they claimed to be a “generation Z voter” who wants a “proper Brexit but the conservatives party ruined”.

The account claimed to be working “with Reform UK” in order to “help them win and spread their values across the UK”.

The person who had been messaging me provided no evidence to support this claim – and a Reform UK spokesperson said this profile was not connected to the party at all. Reform UK told the BBC it had been in touch with social media companies about other accounts falsely purporting to be connected with the party.

Some responses to my messages from GenZbloomer sounded like parody – describing how they would have to speak to a Reform Party county organiser before they spoke to me, but adding that it “should not be an issue Reform has a super lax vetting process”.

After a back-and-forth over text message, my phone number then appeared to have been blocked.

Social media users now seem more likely to accuse other accounts of being bots – alleging they undermine trust and disrupt the online debate, even when some of these profiles turn out to be genuine.

In the past decade, there have been documented attempts by hostile foreign powers, such as Russia, to sow division and promote particular points of view during Western elections. They have used networks of what social media firms call “inauthentic accounts” and what users call bots or “troll farms”. Whether the actions of these accounts changed anyone’s mind is unclear.

In recent weeks, Reform UK has seen a genuine rise in the polls – which may partly explain its growing role in the online conversation.

A spokesman for Reform UK told the BBC: “We are, of course, delighted about the organic growth of online support, but with that come some accounts that are not formally associated with the party, but actively subvert and lie about who we are.”

The spokesman said some people wrongly believe the only way others could end up supporting Reform UK was if they had been fooled in some way by the internet.

In total, I found more than 50 profiles that had the hallmarks of inauthentic accounts, posting in support of Reform UK across the different social media sites – although they could still have been genuine.

These hallmarks can include a username and profile picture with no identifying features, no followers or seemingly real friends – and engaging entirely with political or divisive content, or reposting the same repetitive phrases.

Some had no posts of their own. Others, seemingly based outside the UK, previously posted about US politics and sports or animal cruelty before switching to Reform UK. Several had also shared conspiracy theory content about Covid-19 or posts opposing Ukraine and supporting Russia.

I have not found other accounts posting about other political parties in the same way – or being met with the same accusations.

Many of these accounts did not respond when I contacted them. But one called username341317847855 did. He said his name was Martin and he agreed to speak to me on the phone from the quiet of his van in London.

“Of course I’m a real person. I’m just fed up with the government. I’m fed up with MPs,” he said. He made light of the bot claims, joking that I could call him “Martin the Bot” and telling me he was not worried that these accusations might undermine Reform UK’s social media posts.

Martin said no political parties or users have encouraged him to post. He said he decided to vote for the first time in this election.

Several more of these accounts told me they were real people based in the UK, who were just sharing their political views. Some shared evidence with me to demonstrate this.

One account run by someone called Matt said: “I can assure you I’m not a bot. I’m politically homeless.”

He said he was from Bury, was aged 46 and a welder by trade. He does not have any profile picture or posts on his TikTok account, only comments on the videos of others.

He told me that no political party or anyone else had instructed him to comment in support of Reform UK.

Matt said that when he saw the other profiles posting these comments similar to his on social media, it helped him and others realise “they are not the only ones who feel this way and have these views”.

What Matt’s experience seems to show is that comments that boost the perceived support for a political party – whether they come from UK voters or inauthentic accounts – can embolden more real people to join in.

It is one more piece of evidence in this election that suggests individual social media users and anonymous accounts have the ability to shape the online conversation just as effectively as the content coming from the political parties themselves.

A TikTok spokesperson has previously told the BBC it has introduced “more policies to aggressively counter foreign election interference”.

“Creating fake accounts or engaging in inauthentic activities goes against Meta’s policies”, a spokesperson for Meta, which owns Facebook and Instagram, told the BBC.

X, formerly Twitter, said they “remove accounts engaged in platform manipulation”.

The Undercover Voters are fictional profiles designed to represent a range of voters in battleground constituencies across the UK. They follow, view and like content relevant to their character, informed by data and analysis from the National Centre for Social Research.

For this story, I examined the feeds of the profiles of some of these fictional voters in the constituency of Bridgend in Wales, which is currently held by the Conservatives and is a Labour target.

Gavin – a right-leaning voter in his 60s who has a strong interest in politics – has had content about Reform UK actively recommended to him across his social media feeds, including material with the alleged bot posts in the comments.

On the other hand, 72-year-old Eluned – a left-leaning Welsh Nationalist who is very supportive of the European Union – has been pushed several posts and comments from people concerned that these profiles supporting Reform are bots.

Lily, 18, is not really into politics. Her feed is filled with content about Taylor Swift.

[ad_2]

Source link freeslots dinogame telegram营销