[ad_1]

By Chris Mason, Political editor • Henry Zeffman, Chief political correspondent

BBC

BBCThe moods of the two main parties’ general election campaigns do not tell us what will happen on 4 July.

But as we pass the halfway stage in the long slog to polling day, they do give us a strong flavour of how candidates, strategists and officials think this election is going for them.

And right now, the moods of the Conservative and Labour campaigns could not be more different.

Even the most fatalistic Labourites, for so long determined to avoid complacency, are beginning to admit that they believe government is within their grasp.

Even the most loyal Sunakites, convinced for so long that during an election campaign voters would see the qualities that they see in their prime minister, are beginning to concede that the long-predicted narrowing of the gap between the two parties simply isn’t happening – at least not yet.

“Utterly dire” was the stark response from one prominent Conservative to the campaign so far, “there’s no clear messaging or strategy.”

They decried “the Kool-Aiders” working for Rishi Sunak who, they said, were not realistic about his strengths and weaknesses before thrusting him to the centre of what has so far been a presidential-style campaign.

Soft Labour vote?

Some Conservative candidates argue that the election result will be closer than many expect.

But privately few even half-heartedly mount an argument that the overall outcome is up for grabs anymore.

One candidate said that the prevailing pessimism in the party had sparked a vicious cycle.

“People just stop campaigning,” they said.

“A lot of colleagues haven’t really worked their seats before. When morale is down you can’t really do anything.”

Another influential Conservative made a similar argument.

At the grassroots level, they said: “It’s quite a low-motivation, low-energy campaign. Volunteers are down, lots of Tory MPs who think they are going to lose their seats aren’t really bothering. And that makes it quite difficult inside the campaign to know what’s really going on.”

Some Conservatives insist, though, the true picture of national support is nowhere near as dire as some models projecting a near-wipeout would suggest.

“The Labour vote is softer than people think,” one source said.

“In parts of England the solid Labour vote – people who say they’re definitely voting Labour – is no different to 2019.

“What is different is there’s many, many, many more undecideds who were Conservatives. The problem is how do you get those people to come out when apathy is pretty high?”

Farage’s poll glee

The new message piloted by Grant Shapps, the defence secretary, warning of the consequences of a vast Labour majority, may have been targeted at finding ways to give those persistent undecideds a reason to vote Conservative.

It was arguably the biggest moment of this third week of the campaign and a strategy from a campaign that feels like it has run out of better ideas.

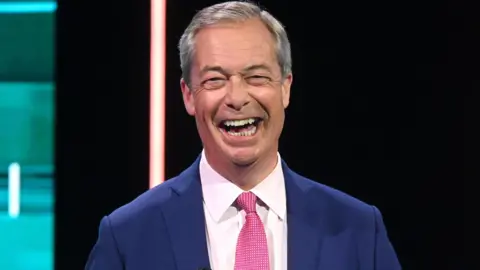

Nigel Farage’s decision to become leader of Reform UK and run for a seat himself was one of the biggest moments of the campaign so far.

The Conservative Party’s worst nightmare came true.

On Thursday evening, minutes before ITV’s latest election debate started, a YouGov poll appeared putting Reform UK one percentage point ahead of the Conservatives for the first time.

Not surprisingly, Mr Farage seized on this with glee, telling the ITV audience: “We are now the opposition to Labour.”

“This is the inflexion point. The only wasted vote now is a Conservative vote,” he added in an online video.

It is only one poll, and 1% is within the margin of error. Let’s see what others suggest in the coming days.

But psychologically it is the last thing the Conservatives need.

ITV/PA

ITV/PAIn Labour, meanwhile, there is a tangible buoyancy.

Campaign insiders say that the first three weeks have gone smoothly, but insist that this is not the product of springing into action after Mr Sunak’s sudden decision to go to the polls.

“Things are going well because of how carefully crafted things have been for a long time,” one campaign source said.

“That’s a step change in standards, in professionalism. It’s the cultural change that Keir has brought. Everything is done properly.”

The Labour campaign has not been without its wobbles.

The saga over whether Diane Abbott would be a Labour candidate disrupted the party’s news “grid” and there was frustration at the top of the party at Sir Keir Starmer’s failure to immediately rebut Mr Sunak’s tax attack in the first televised debate last week.

“In some ways that was good for us because it reminded people that not everything will go to plan,” a senior official said.

To some on the left of the Labour Party – as signified by a protester early on in Sir Keir’s speech at the manifesto launch – the absence of radical new policies in the manifesto risks depressing turnout among leftwingers.

Sir Keir embraced that critique in his speech, saying the stability in his programme was evidence of the stability he would bring to government.

That’s why Labour chose to launch their manifesto at the same venue in Manchester where Sir Keir unveiled his “five missions” for government in February 2023, with messaging substantially the same as today’s.

Labour prepares for power

Reuters

Reuters So what next for the Labour campaign?

The party is proud of its so-called “ground war” – the pavement pounding, door knocking and leafleting that goes on away from the cameras.

Privately, the party reckons its operation and data gathering is far superior to the Conservatives’.

As for the “air war” – what you will see in media coverage – it will be the same kinds of events and certainly the same message.

But Sir Keir’s visits will be taking place over the coming days in constituencies with larger Conservative majorities than those he has visited so far, the BBC understands – a clear display of confidence.

Activists, too, are being encouraged to focus their energies on more and more ambitious target seats.

One curious twist coming in the next few weeks, not lost on senior Labour people, is the start of the Euros, the football tournament.

This will command attention and passion, disrupt television schedules and distract people at just the point the election campaign reaches its crescendo.

How to campaign, in an inevitably partisan manner, as people, particularly in England and Scotland come together to watch the football, poses a challenge.

Some at the top of the Labour Party are beginning to think, if a little furtively, of the aftermath of 4 July, too.

Senior staff still do not know for sure what jobs they would have in Downing Street if Labour win but Sue Gray, Sir Keir’s chief of staff, has spent most of the campaign at party headquarters preparing detailed plans for government.

Some shadow ministers have taken time off the campaign trail to hold “access talks” with civil servants in Whitehall.

There are logistical questions about a Labour government, too.

For example: would they let MPs take their traditional six-week summer recess?

While plans are not yet developed on this, the answer appears to be a resounding no.

“We can’t pass up the opportunity to hit the ground running,” one Labour source said.

[ad_2]

Source link freeslots dinogame telegram营销