[ad_1]

By Vicki Young, BBC Deputy Political Editor • Carolyn Quinn, BBC News • Jonathan Brunert, BBC News

PA

PAFormer home secretary Suella Braverman has told the BBC she still has the 24-hour personal protection she was given while in government because of the threats and harassment she receives.

On a recent trip to a supermarket, she said people called her “a genocidal bleep” in front of her children.

The government announced a £31m budget for security for politicians in February.

The extra money follows the murder of MPs Jo Cox in 2016 and Sir David Amess in 2021.

For the first time, all election candidates now have access to panic alarms and a named police contact to liaise with on security matters.

All requests for help are assessed by the Home Office within 24 hours, according to government sources.

It comes as there is a growing sense of fear among politicians about violent attacks.

Ms Braverman told the BBC the incident at the supermarket was “aggressive, abusive and intimidatory and harassing” and she was followed to the checkouts.

“It’s obviously about the issue to do with Israel and Hamas. And a couple of people came very close up to me. They said ‘Hey, this is Suella Braverman. You’re a genocidal bleep’.”

She said the people calling her names then phoned their friends to join in the abuse, but she was able to be insulated by her security and the situation was diffused.

Pro-Palestinian activists also found out where her husband worked and sent him abusive phone messages, she said.

Feeling passionate about an issue is no excuse for violence, she added “It’s not an excuse to tell someone you’re going to kill them or rape them or kill their child.”

It’s also “incredibly offensive” to suggest that she’s brought this kind of abuse on herself by being outspoken, she said.

“I’ve never incited violence. I’ve never threatened to attack anybody. I’ve never encouraged anybody to be violent. I have set out very legitimate views, about political issues because I’m a politician and it’s my job to do so.”

Stab vest and flak jackets

Politicians run for office knowing that they’ll be in the public eye and would expect to draw criticism.

But the examples politicians have described are horrifying: rape threats, murder threats, misogynistic, racist and sexist comments, coming via social media, email and sometimes face-to-face.

The issues sparking this abuse are varied. During the Brexit referendum, Conservative Rehman Chishti was grabbed around the throat at a street surgery. He, like many others, now follows police advice not to advertise surgery locations in advance.

Some have been reluctant to speak out because they think it will encourage more attacks. Others have decided it’s time to say the threats, abuse and physical attacks are having a detrimental effect on democracy.

It was in 2016 that Labour’s Naz Shah received her first death threat. She remembers receiving a call from the police who told her there had been a threat to shoot her.

“At that point, I did sit my daughter down. She was only 13. I wouldn’t wish any 13-year-old having to have that conversation with your mother saying ‘look, if anything happens to me, you remember your mother was doing the right thing’.”

Like many former MPs, she carries a panic alarm, checks in with the local police at least twice a day and has security measures in her offices and at home.

Her children had to be briefed about what to do if they were in danger, how to use the panic alarms and how to communicate with the police using agreed safe words.

UK Parliament

UK ParliamentThere’s no doubt that events in the Middle East have heightened tensions in many constituencies.

One senior Labour figure said there were areas they could no longer visit, shop in or meet people because of the intensity of anger they would face.

Former MP Conservative Tobias Ellwood, who is standing again at this election, told the BBC he keeps a stab vest and flak jackets in his car.

Before becoming a politician he served in the Royal Green Jackets regiment of the Army and he said of his current situation: “I’m having to put on my military head again to deal with a civilian world. It just doesn’t seem right..

In February, as Parliament was preparing to debate the Israel Gaza crisis, he was called by his local police force and told not to go home because there was a demonstration outside his home.

Activist Corrie Drew, who helped organise the protest, says civil disobedience and direct action, as long as it’s not violent, is a way to get the conversation going.

“He wasn’t actually home at the time. …and the fact that us shouting outside his house for a couple of hours and causing very little disturbance… was highlighted as being the problem, rather than the thousands of murdered Palestinian children, makes me think that Tobias Ellwood must have absolutely no heart whatsoever.”

But Mr Ellwood said that, for the first time, he now needs security at some public meetings which adds “a rather toxic, unnerving dimension to the general election”.

Heightened tensions

Parliamentary candidates on the campaign trail face different kinds of hostility. Reform UK leader Nigel Farage has been covered in milkshake and had hard objects thrown at him while campaigning.

Other candidates say they’ll no longer attend hustings due to fears about personal safety.

Danny, a security advisor who has worked with many MPs, has nearly two decades of experience with the military and in the private sector and says that while eggs, flour and milkshakes being thrown are minor, all threats have to be taken seriously.

“We can’t take any threat regardless of how small it is lightly, because it’s that time you don’t pay attention, that’s when something serious could happen.”

Once elected, an integral part of an MP’s job is being accessible to constituents who are seeking advice. Many parliamentarians say they’ve had to change the way they work in order to protect themselves, their families and their staff. Some don’t see constituents alone.

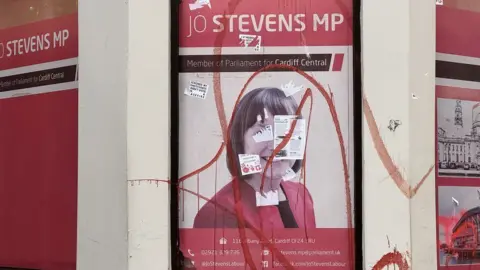

Labour’s shadow Welsh secretary, Jo Stevens, had her constituency office vandalised last November. Effigies of bloodstained babies were left on the doorstep with candles and photographs of the violence in the Middle East were pushed through the door with abusive messages.

She says everything is now done by appointment and there are security checks on the door, but worries that barriers are being put in the way of those in need.

“I have a very high immigration caseload…and the people that need help are not going to come if they have to make an appointment and it feels official. They want to be able to drop in and get help,” she said.

A number of MPs who’ve decided to leave Parliament at this election have specifically mentioned the abuse they’ve received as a key reason for stepping away from politics. Those who want to continue, like Jo Stevens, regret that intimidation is changing the way that they feel they can now safely do the job.

Violence directed at MPs is nothing new but speaking to those with years of experience around Westminster there’s a sense that it’s become far more widespread, almost part of the job description.

As well as the threat to personal safety there are broader ramifications for our political system. Potential candidates for public office could be deterred from standing and MPs have already changed the way they interact with constituents.

MPs say they’re not looking for sympathy and accept they must face legitimate scrutiny and robust debate.

But some fear the increasingly aggressive nature of political discourse could stop Parliamentarians openly expressing their views, to the detriment of the whole political system. As Naz Shah put it, “it’s deadly for democracy itself.”

Getty Images

Getty Images[ad_2]

Source link