[ad_1]

By Ros Atkins, BBC News Analysis Editor

All election nights have their defining moments.

Some, such as the shock of then Defence Secretary Michael Portillo losing his seat in 1997, lodge in our minds and are referenced for many elections to come.

As the dust settles on election night 2024, the “Portillo moment” may have been eclipsed.

At 06:48 BST on Friday 5 July, former Prime Minister Liz Truss lost her South West Norfolk seat by just 630 votes, overturning her majority of more than 26,000.

She had arrived at the count just seconds before the result was declared – to the sound of a slow handclap – and was quick to leave, departing with only a few words.

You’d have to go back to 1935 and Ramsay MacDonald to find a former PM losing their seat in Parliament. This isn’t normal in UK politics.

Inside a leisure centre in King’s Lynn, I witnessed Liz Truss’ defeat and spoke to her directly afterwards – her only comments since that moment.

Here’s how a night of extraordinary tension unfolded.

‘The story of the night is about to happen’

At the 2019 general election there had only been a handful of journalists at this count. This time round, tables for the media stretched along one side of the hall.

None of us knew if Ms Truss would lose her seat but we knew her 49 days in office in 2022, and the turmoil in the financial markets that came with it, were one of the reasons the Tories were under severe pressure.

At these counts, representatives of the parties – known as counting agents – can stand by the tables as the votes are sorted and tallied.

PA Media

PA MediaJournalists aren’t allowed too close but, from a couple of metres back, can watch the votes and talk to counting agents or even candidates.

By 3am we were getting a consistent message.

The Lib Dems, Greens, and Labour were all saying Reform were exceeding expectations and that it was tight – between Ms Truss, Labour and Reform.

News of high profile Conservative scalps came in: Penny Mordaunt, Jacob Rees-Mogg, Grant Shapps and others. In all, 12 cabinet ministers would lose their seats.

However, Ms Truss was in a particularly comfortable position.

South West Norfolk has elected a Tory MP for decades and was one of the safest Tory seats in the country.

First light was now coming through the double doors where earlier the ballot boxes had been carried.

At the front of the leisure centre, a small group of journalists waited for Ms Truss’ arrival. “I’ve never had a welcome like this before,” quipped one man in shorts as he arrived to use the leisure centre.

Outside, Earl Elvis of East Anglia, the Monster Raving Looney Party’s candidate, stood alone, smoking a cigarette. A few metres away, the Labour candidate Terry Jermy was looking intently at a piece of paper. He appeared to be practising a speech.

Liz Truss, though, still hadn’t arrived.

My colleague Chris Gibson was soon told by an election official that she had definitely lost.

He showed Chris a message he’d sent his wife: “Turn on the TV. The story of the night is about to happen.”

Some in the hall knew the result; most, I think, did not.

I repeated back to Chris exactly what I planned to say on air, not wanting to get a word wrong.

Suddenly, as I started talking to the camera, everyone was listening.

“We have received a strong indication that Liz Truss has lost,” I told BBC viewers. Some people near me gasped, others cheered.

With all the other candidates present and the result now widely known, Ms Truss’ absence was causing frustration. The slow handclap began.

Minutes later, two cars swept into the car park and she emerged from one of them.

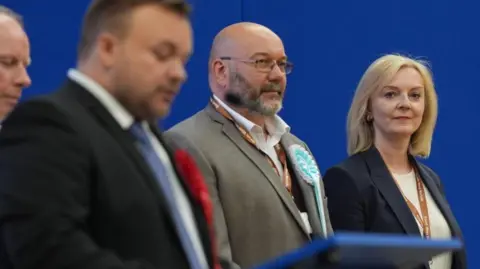

The other candidates were already on the stage. Ms Truss took her place by Toby McKenzie of Reform, who only got into politics in the last few months. He and the former PM would end up fewer than 1,500 votes apart.

I was standing five metres from Ms Truss as Labour’s narrow victory was declared.

Throughout, Ms Truss stared ahead impassively, arms straight at her sides.

PA

PACheers broke out as Terry Jermy stepped forward as winner. He shook Ms Truss’ hand, shook the hands of three other candidates and made the speech he’d rehearsed in the car park.

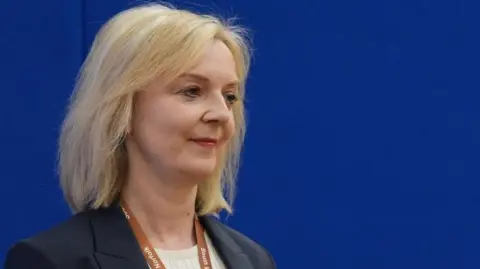

After the speech, the returning officer shook Ms Truss’ hand. We wondered if there would be a concession speech. We immediately got an answer.

Liz Truss turned away from the lectern and stepped off the stage.

“Give me a few seconds to say hello to people,” she told me. A brief conversation with her husband followed, and, good to her word, she came back.

And so – with a sign that read “goals should be hung up when not in use” behind us – we began.

‘I’ve got a lot to think about’

Did Ms Truss take responsibility for what was happening to the Conservatives because of events during her time as prime minister?

“I think the issues we’ve faced as Conservatives is that we haven’t delivered sufficiently on the policies people want.

“And that means keeping taxes low but also particularly on reducing immigration.”

I noticed that she spoke of the Conservatives’ actions but not of her own.

Wasn’t Ms Truss in the cabinet and, for a time, prime minister while the Conservatives failed to deliver on key policies?

For a beat, she looked at me, then replied: “I agree I was part of that, that’s absolutely true.”

Then there was a look back to Labour’s last time in power.

“But during our 14 years in power, unfortunately we did not do enough to take on the legacy that we’d been left.”

I wanted to know if Ms Truss planned to stay involved in Conservative politics.

“I’ve got a lot to think about,” she replied and with a hint of smile added, “I haven’t slept last night so give me a bit of time, but I will definitely talk to you again when I’ve got the opportunity.”

But there was, though, one more question it felt important to ask there and then.

Did Ms Truss want to say sorry to the people of Norfolk?

Ms Truss didn’t answer.

I asked once more. Did she have a message for supporters of the Conservatives? Or to the country?

“I’ve answered your questions. Thank you,” Ms Truss replied.

PA

PAIn the tiny entrance way of the leisure centre, her staff had gathered, most wearing a blue rosette with Liz Truss’ name in the middle. She stopped to hug each of them. Some looked devastated, all looked shocked.

Then, with a turn, ahead of everyone else, Ms Truss stepped out into the morning. Away from the count, away from her colleagues and, for now, away from her political career.

I made one last effort to ask if she had anything to say to voters. There was no reply.

Ms Truss climbed into the car. A security officer just beside me shut the door firmly behind her, and a small group of us looked on as the two vehicles drove out of sight.

Historic moments come in many forms. This one played out on the badminton courts of King’s Lynn, as a former prime minister lost her seat – and had little to say to voters or the country she’d once led.

[ad_2]

Source link freeslots dinogame telegram营销