[ad_1]

Ove Hoegh-Guldberg

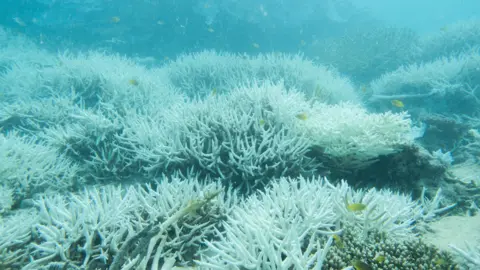

Ove Hoegh-GuldbergA study of samples taken from inside the bodies of centuries-old coral has revealed the threat climate change now poses to the Great Barrier Reef.

Researchers in Australia say temperatures in and around the vast coral reef over the past decade are the highest recorded in 400 years.

Extreme heat has already caused five mass bleaching events in the past nine years alone.

Writing in the journal Nature, the scientists behind the study say increased temperatures, driven by climate change, now pose an “existential threat” to this natural wonder of the world.

Deb Henley

Deb Henley“The science tells us that the Great Barrier Reef is in danger – and we should be guided by the science,” Prof Helen McGregor, from the University of Wollongong, told BBC News.

The new evidence comes from within the coral itself.

Over many years, marine scientists have collected cores – samples drilled out of the skeletons of coral – which provide chemical clues about how the environment around the reef has changed as the coral developed.

Coral – which are animals, not plants – can live for centuries, laying down chemical indicators about their natural environment.

Researchers in Australia re-examined the data from thousands of these cores and cross-referenced them with historical sea temperature records from the UK’s Hadley Centre.

The research showed temperatures around the Great Barrier Reef in the previous decade were the warmest of the past 400 years.

Tane Sinclair-Taylor

Tane Sinclair-Taylor“The recent events in the Great Barrier Reef are extraordinary,” said lead researcher Dr Benjamin Henley, who carried out the study whilst working at Wollongong University.

“Unfortunately, this is terrible news for the reef.”

“There is still a glimmer of hope though,” he added. “If we can come together and restrict global warming, then there’s a glimmer of hope for this reef, and others around the world, to survive in their current state.”

Corals have adapted to survive and grow within a specific temperature range – forming a skeleton that provides a living habitat for other marine life.

Corals exist in a symbiotic partnership with a special type of marine plant – an algae – which lives inside the coral, providing it with food and giving it its bright colour.

Bleaching occurs when sea temperatures rise too high and corals expel their algae, subsequently turning white.

“It’s not a pretty sight,” said Dr Henley. “Eventually [other] algae grows on the surface of the white coral, turning it brown.

“While bleached coral can recover, if the heat does not relent, it doesn’t have the chance to,” he explained.

‘Huge signal’

“I’m a little reluctant to say things are doomed,” said Prof McGregor.

“Reefs have survived a lot of change over geological time. So I guess the question comes down to – what kind of reef do we end up with?

“It won’t be like what we have now.”

The Great Barrier Reef is currently a Unesco World Heritage site. Scientists hope that this research could persuade the UN organisation to change its mind and give the reef official “endangered” status.

Prof McGregor said this “would send a huge signal to the world about how grave the problem is”.

“We know what we need to do,” she added. “We have international agreements in place [to limit global temperature rise].

“I think we just need to put the politics aside and get on with it.”

[ad_2]

Source link freeslots dinogame telegram营销