[ad_1]

Mark Gridley/Oxford Archaeology

Mark Gridley/Oxford ArchaeologyImagining Roman Britain conjures up images of emperors, gladiators, posh villas – and the army that held the empire together.

But a much more varied story is emerging, thanks to evidence uncovered by excavations in recent years.

Beer brewing was just one of the industries that grew rapidly to supply the military, and small towns and cities like Camulodunum (Colchester) and Verulamium (St Albans) in the three-and-a-half centuries of Roman rule.

So, what have these digs revealed about daily life in Roman Britain?

From invasion to industrialisation

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIt took the Romans about 45 years to take over most of England and Wales after they invaded in AD 43, arriving in a disunited land dominated by tribal leaders.

The need to supply their army was the “key driver”, according to archaeologist Edward Biddulph, as well the urban centres they created. This led to the rapid industrial development.

The Oxford Archaeology senior project manager said pottery, building materials, metalwork and glass were all being produced across the country, but from the 3rd and 4th Centuries “we start to see mega industries”.

“We know industrial activity was undertaken at a very large scale at a number of sites in Roman Britain and we have some very large sites that are helping us to really fill in the gaps in our knowledge, the missing pieces that we’ve long been struggling with,” he said.

“One of the classic areas is malting and brewing, if you look at Roman Britain you see next to nothing about this, yet people must have been drinking beer.”

Romano-Britons made a lot of beer

Oxford Archaeology

Oxford ArchaeologyEvidence of brewing on an industrial level was discovered at a Roman villa at North Fleet in Kent, and using the features found there – such as malting ovens and lined tanks for steeping the grain – archaeologists knew what to look for at smaller sites.

One of those was Berryfields, a development near Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire, excavated between 2007 and 2016.

“Oven-like structures” often found at Roman settlements had previously been believed to be used for drying corn.

Oxford Archaeology

Oxford ArchaeologyMr Biddulph said now they are “recognised as malting ovens, used to heat partially germinated grain to produce malt”.

“At Berryfields, we found evidence of malting and brewing and the tanks used to steep the grain before processing,” he said.

“We tend to think of the Roman world as being very much a wine-loving place.

“But actually a lot of the population in Roman Britain were drinking beer and we see that in the pottery they were using, large beakers in the same sort of sizes as modern pint glasses.”

Sea salt and fish sauce

Another industry that began producing on an industrial scale was discovered at Stanford Wharf Nature Reserve, near Thurrock in Essex, in 2009.

The excavation revealed salt had been extracted there from the Iron Age, but that really ramped up in the 3rd and 4th centuries.

Mr Biddulph said: “Salt was one of the most important commodities in the Roman world, not only used for flavour and to preserve food but in religious activity and for cleansing.

“In fact the Roman author Pliny the Elder said ‘Civilised life can’t proceed without salt’.”

Oxford Archaeology

Oxford ArchaeologyWith its location on the Thames estuary, the salt was probably exported to London, but also across the rest of the country and abroad. The county still hosts the industry, as the home of Maldon Sea Salt.

“And actually, more excitingly there was evidence that they made a fermented fish sauce, and fish sauce was like the Roman tomato sauce, that they used on absolutely everything,” Mr Biddulph said.

For centuries, the sauce had been imported from Spain, but after that industry collapsed it looks like the Essex manufacturer stepped into the gap.

Villa estates as industrial hubs

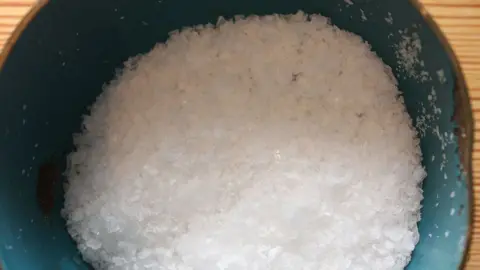

Mark Gridley/Oxford Archaeology

Mark Gridley/Oxford ArchaeologyThe 3rd Century onwards saw the establishment of large “villa estates”, said Mr Biddulph.

The driver for that seems to have been the need to feed the Roman army, especially the soldiers stationed along the River Rhine in present-day Germany.

These estates also had their industrial areas, as an excavation near Corby, Northamptonshire, revealed in 2020.

Oxford Archaeology

Oxford ArchaeologyEvidence of pottery, ceramic building material such as roof tiles and bricks and lime, were unearthed but “a tile kiln was an exceptional discovery”.

He said: “One of the features was a nice, really well-made engineered army-built road.

“There was no Roman fort there, but it just shows how connected these villa owners were to the elite and having their own army-built road really shows this.

And in a glimpse of its long-dead inhabitants, the imprint of a woman’s sandal and animal footprints were found on some of the tile rejects, while another tile had a finger-made inscription.

Major pottery production centre

Oxford Archaeology

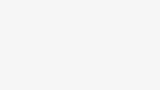

Oxford ArchaeologyGoods like olive oil and wine were imported to Britain using large ceramic jars known as amphora, but Romano-Britons “produced their own big jars which could rival this pottery”, said Mr Biddulph.

A 2021 excavation at Horningsea, next to the River Cam in Cambridgeshire, revealed it was a major pottery production area.

Mr Biddulph said: “Its most distinctive aspect was the production of very large jars.

“These may have been a specialist line, but it is unclear whether they were associated with a specific commodity, as transport containers, perhaps for flour, or whether they were simply a particularly successful form of all-purpose storage jar.”

What he does believe is the pottery was producing the jars were most likely to have been used in the vicinity, unlike the imported amphora.

And what about the people who toiled in these industries?

“It’s a tricky question because we don’t have the evidence, but it was probably not just the enslaved, but a range of people,” said Mr Biddulph.

“And it was a pretty tough life, not particularly pleasant, where ever you were on the social scale.”

Oxford Archaeology

Oxford Archaeology[ad_2]

Source link