[ad_1]

SWNS / BBC

SWNS / BBCThe Church of England made a six-figure pay-off to a priest assessed as a potential risk to children and young people, a BBC investigation has found.

A senior member of staff at Blackburn Cathedral resigned over the settlement and says concerns about the priest were “an open secret” among senior clergy.

Canon Andrew Hindley – who worked in Blackburn diocese from 1991 to 2021 – was subject to five police investigations, including into allegations of sexual assault.

He has never been charged with any criminal offences and says he has never presented any safeguarding risk to anyone.

The archbishops of Canterbury and York have told the BBC they are “still working” to get Church processes right and “must learn” from past mistakes.

The former Bishop of Blackburn Julian Henderson described the financial settlement when he was in post as the “only option” left for the Church “to protect children and vulnerable young people from the risk Canon Hindley posed”.

File on 4 – The priest and the pay-off

Over three decades a priest assessed as posing a risk of “significant harm” to children and vulnerable people worked in the Church of England. But allegations against him didn’t stick, leading to him remaining in post until after he was offered a substantial pay-off. The surprising manner in which he finally left in 2022 raises serious questions about the judgement of Church leaders.

Despite many people we approached being unwilling to talk, our two-year investigation also found:

- Restrictions on Canon Hindley, banning him from choir school and school visits, were never monitored

- The Archbishop of Canterbury, the Most Reverend Justin Welby, backed a plan to close Blackburn Cathedral if the priest returned to work from suspension

- Three Lancashire bishops complained “strings have been pulled and networks have been used to effect Canon Hindley’s ongoing ministry”

- There were previous attempts to pay the priest to leave, dating back more than 15 years

The pay-off

In 2022, Canon Hindley was offered £240,000, the BBC understands. We do not know the final amount paid because the parties signed non-disclosure agreements keeping it secret.

The Church of England said it was settling legal action brought by the priest in response to an earlier Church decision to force him to retire.

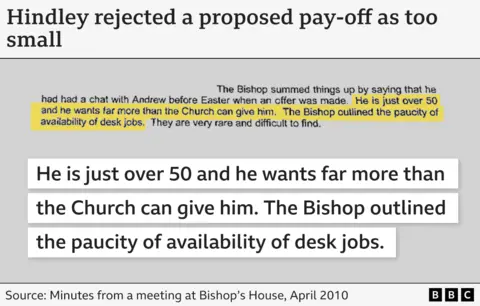

But the BBC has seen evidence the Church tried several times over the years to pay off Canon Hindley.

It was the “tipping point” for Rowena Pailing, who quit as the cathedral’s vice-dean and head of safeguarding, ending a nearly 20-year career with the Church of England.

“I couldn’t work for an organisation which put its own reputation and the protection of alleged abusers above the protection and care and listening to victims and survivors,” she tells the BBC, speaking publicly for the first time about the case.

The message the payment sends to victims and survivors is “absolutely horrific… I was devastated”.

Steve Swann / BBC

Steve Swann / BBCMrs Pailing says that when she was offered the job in 2018 she was warned of “serious safeguarding concerns and allegations” over a priest, spanning “a long period of about 25 years”.

She says she was assured there was a plan to deal with it. But after taking up the post “it became quite clear there was no plan” and quickly realised the Church of England was sitting on an open secret.

Recalling an event at Lambeth Palace, home of the Archbishop of Canterbury, she says: “There was a bishop from another diocese who referred to the particular canon by name and asked if he was still up to his old tricks.”

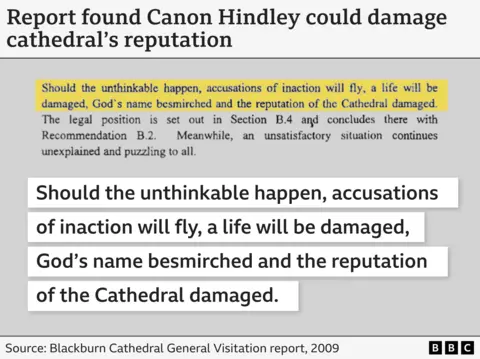

Internal Church of England documents, seen by the BBC, show there had been concerns about Blackburn Cathedral for years.

A 2009 cathedral inspection concluded Canon Hindley “may pose a threat to young men” and to the cathedral’s name.

Over the years, Lancashire Police opened five investigations into Canon Hindley:

- 1991: Allegation of sex with a 17-year-old boy when the age of consent for gay men was 21

- 2000: Allegation of sex with a 15-year-old boy when the age of consent was 16

Both investigations were dropped after the alleged victims and the canon denied the allegations.

Police took no further action in three other investigations. In each, Canon Hindley denied the allegations:

- 2001: Allegation of sexual assault of a teenage boy three years earlier – a later report commissioned by the Church shows Canon Hindley had been accused of giving the alleged victim alcohol, encouraging him to watch pornography and touching his genitals

- 2006: Allegation over remarks made to a 15-year-old boy

- 2018: Allegations of sexual assaults at a party in the cathedral garden

Lancashire Police says it assessed all available information and “where evidence was available investigations were undertaken and advice sought from the Crown Prosecution Service” but that “this did not result in any charges being brought”.

As well as police investigations, church leaders, with a duty of care to churchgoers and staff, commissioned several expert risk assessments into whether Canon Hindley posed a safeguarding risk.

The repeated failure to definitively act on the findings of these risk assessments, and other warnings, is at the centre of our investigation.

The Cathedral did suspend Canon Hindley at least twice and banned him from choir school, junior confirmation groups and school visits. But – according to a document we have seen – “the restrictions were never monitored”.

‘Teflon priest’

For years, he remained as Canon Sacrist, planning services and managing the vergers and servers, while living in a cathedral townhouse.

SWNS

SWNSA review of cathedral residence arrangements in 2020 noted colleagues nicknamed him “Teflon”, implying complaints or allegations would never stick.

Canon Hindley claims he was subjected to a campaign to drive him from the church “which was motivated by homophobia and personal agendas” and “the Church has allowed its safeguarding procedures to be hijacked, weaponised and misused”.

Also in 2020, a report by a consultant clinical psychologist concluded there was “low to moderate risk of future inappropriate sexual behaviour” with risk increasing if Canon Hindley spent “prolonged periods of time alone in the company of young males”.

It was the last in the series of risk assessments.

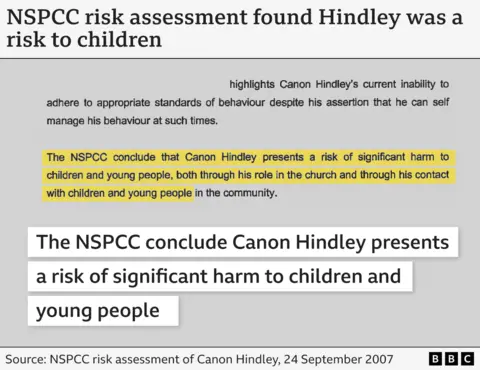

Thirteen years earlier, the children’s charity the NSPCC had said Canon Hindley presented “a risk of significant harm to children and young people” and advised he “should have no unsupervised contact with children or young people”.

It also recommended he attend a sex offender programme and his risk be reassessed – and if he failed to co-operate, the Church should think about ending his employment.

The priest challenged the findings.

A review he commissioned by a social work researcher in 2007 said “it would be hard to sustain an argument of predatory targeting behaviour” but Canon Hindley “needs support on developing his boundaries in relation to work with children”.

A judge also made some criticisms of the report, while considering an unrelated case. Referring to the criticisms, Canon Hindley has told the BBC the judge concluded the authors of the NSPCC report had failed to properly understand their role and remit and appeared to “equate homosexuality with a risk of paedophile abuse”.

In 2017, Canon Hindley was offered a job in another diocese – but it was withdrawn after a risk assesssment found “significant safeguarding risks”. He remained in post at Blackburn.

‘CofE not safe’

Child protection expert Ian Elliott says our investigation exposes a clear failure to act on information presented by experienced professionals who had warned of the potential for significant harm.

BBC / Steve Swann

BBC / Steve Swann “When you’ve commissioned a risk assessment, you’ve done it for a reason,” says Mr Elliott, who has carried out safeguarding reviews of religious institutions across the world.

“I do not feel the Church of England is safe.”

As a means of removing Canon Hindley, the Cathedral Chapter governing body voted in January 2021 to retire him on ill-health grounds, using an untested law from 1949. But he brought a claim in the High Court for judicial review of that decision.

The cathedral then began legal proceedings to remove him from his cathedral townhouse, which he also opposed.

Steve Swann / BBC

Steve Swann / BBCThis pushback may explain why church leaders had not acted earlier. Internal papers show they had previously considered dismissing Canon Hindley but were worried about legal action.

He was one of a small number of clerics holding what is called a freehold office which was abolished for new priests in 2007 and gives a more protected status than that of a regular employee.

Rowena Pailing says that for senior clergy and the Church’s legal team, “the fear that was always named was a fear of litigation”.

Blackburn diocese has told us that, prior to his forced retirement, it “explored every single option” for removing Canon Hindley but the only way it could have happened was if a complaint against him had been upheld at an internal church tribunal.

Several attempts were made to take complaints to tribunals but all were refused permission to proceed.

If allegations are at least a year old, permission from a senior church-appointed judge is needed before they can be heard by a tribunal. Several complaints against Canon Hindley were refused permission by those judges, including two in 2020.

This led Mrs Pailing and other senior cathedral staff to write to the archbishops of Canterbury and York expressing their “profound concern” and asking them to intervene.

The Church of England has told the BBC there was “no way in which they [the archbishops] could lawfully have intervened” in “a judicial decision taken by an independent judge”.

Canon Hindley says that whenever his case has been considered objectively by an independent judicial decision-maker, “I have always been exonerated”.

He claims that the “endlessly recycled false allegations” were all part of a homophobic campaign against him.

Canon Hindley was an openly gay priest in a cathedral which some people we have spoken to describe as “conservative”.

But we have talked to former colleagues who believe he used some of the homophobia he did experience to deflect challenges about his own behaviour.

Alleged victim told ‘move on’

A close family member of one of Canon Hindley’s alleged victims says that the Church had been afraid to act.

She did not want to be identified and would not talk about her relative’s allegations against Canon Hindley.

Joan – not her real name – says when her relative made a complaint of sexual misconduct against the priest, “the first reaction seemed to be one of a fear to take it on”.

“That fear seemed to revolve around the likelihood that the Church could be brought down by this.”

She recalls a letter from a previous Bishop of Blackburn advising the family “to move on”.

“I thought that was quite an offensive thing to say to us. It was like sweeping it under the carpet.”

The family felt “completely dismayed” that their complaint was never tackled, says Joan.

“We don’t know what the outcome would have been. But nobody tried.”

Leaking to press

In 2020 – a year after being first alerted to concerns about Canon Hindley – Archbishop Welby attempted to intervene.

Andrew Graystone, an advocate for survivors of abuse in the Church of England, says he was called by a senior member of clergy from Blackburn Cathedral.

“The Archbishop [of Canterbury] had told them that the Church house lawyers wouldn’t be able to resolve this, and the archbishop himself suggested that one way for this clergyman to go would be to, effectively, leak the story to the press,” he says.

We asked the Church of England to comment on the suggestion of leaking to the press but it did not directly respond.

In the end the idea was dropped. But Church leaders would go on to sanction even more drastic action – as Canon Hindley pushed to return to work, having been suspended pending the police investigation into the sexual assault allegations at the cathedral garden party.

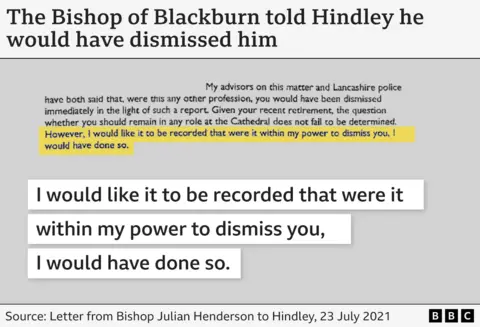

In July 2021, the then-Bishop of Blackburn, Julian Henderson, wrote to the canon saying he would have sacked him if he could, after the final risk assessment had found “the risk of inappropriate sexual behaviour to others as low to moderate”.

Rt Rev Henderson said “this should never be said of a clerk in Holy Orders” and he made the startling threat that if Canon Hindley came back to work he was “prepared to close the ministry of the Cathedral”, with the agreement of the Dean and the archbishops of Canterbury and York.

Ian Elliott says that closing a cathedral “so that you can sideline someone against whom allegations of abuse have been made, is appalling and ridiculous”.

“And if you can’t see that, then there’s a problem.”

Rt Rev Henderson has told the BBC there was no way Canon Hindley could be allowed to return to ministry at the cathedral, and if he could not be prevented from returning, then the only option, albeit drastic, was to shut down the ministry at the cathedral.

“It was the last lever left available to us to pull.”

The BBC has also seen a letter from May 2020 signed by all three Lancashire bishops, complaining to the archbishops that “strings have been pulled and networks have been used to effect Canon Hindley’s ongoing ministry”.

When we asked what this referred to, Rt Rev Henderson told us it was “almost impossible to understand” how a complaint against Canon Hindley had not been progressed to a church tribunal.

“Therefore, it was natural to wonder whether other factors had been called into play that we knew nothing about.”

In the end, the Church’s solution to get rid of Canon Hindley was to dismiss him on ill-health grounds, followed by a financial settlement.

The case “highlighted on the BBC today is complicated and very difficult for everyone involved,” it says.

But the BBC has seen evidence of several previous attempts to pay the priest to leave the ministry, going back to at least 2008. On one failed occasion “the lump sum offered was considered too small” by Canon Hindley, according to a Church document seen by the BBC.

“This individual has actually been paid a sum of money by the Church to retire from their position and to all intents of purposes has not been held to account in any way,” says Mr Elliott.

Speaking to the BBC, the current Bishop of Blackburn, Philip North, says: “I don’t think anybody can be quite happy with the way that that situation was resolved.”

He was not in his current position at the time of the settlement and would not say if it was normal for a priest to be paid after retiring in such circumstances.

“What really matters is the learning from that case, and the steps that we must take as a church in order to be safer into the future,” he says.

At the centre of that are risk assessments.

The Church of England says it is currently reviewing the regulations and guidance for it.

“Priests can have a risk assessment which can indicate a level of risk” and “the powers of a diocesan bishop are limited,” says the bishop.

“Now, that, for me, is a significant area of weakness.

“When a risk assessment indicates a priest has a risk, we should be able to take action.”

In a joint statement with Peter Howell-Jones, the Dean of Blackburn Cathedral, he has said the Church must listen “more closely than ever” to survivors of abuse “to ensure that the Church now, and in the future, is not hampered by its own processes from acting quickly and properly on serious safeguarding matters. Only then can this truly be a safe Church for everyone”.

But Rowena Pailing, who is now adjusting to life outside ministry, says: “Bishops have an awful lot of power and if they want to do something, they can do it.

“[So] I think for many of those senior clergy, when they said that they couldn’t do it, what it meant was that they weren’t brave enough to do it.

“They had 25 years to sort it out. Quite frankly, if you never start the process of change, then of course it’s never going to happen.”

Additional reporting by Fergus Hewison

[ad_2]

Source link freeslots dinogame telegram营销