[ad_1]

Colombian government

Colombian governmentIt has been hailed as the most valuable shipwreck in the world.

A Spanish galleon, the San José, was sunk by the British off the coast of Colombia more than 300 years ago. It had a cargo of gold, silver and emeralds worth billions of dollars.

But years after it was discovered, a debate still rages over who owns that treasure and what should be done with the wreck.

The Colombian and Spanish states have staked a claim to it, as have a US salvage company and indigenous groups in South America. There have been court battles in Colombia and the US, and the case is now before the Permanent Court of Arbitration at the Hague.

The Colombian government says it wants to raise the remains of the vessel and put it in a museum. Treasure hunters point to the commercial value of the cargo, which could be as much as $18bn (£13.bn).

But archaeologists say the wreck – and thousands like it scattered across the world – should be left where it is. Maritime historians remind us that the San José is a graveyard and should be respected as such: around 600 people drowned when the ship went down.

“It’s a great mess and I see no easy way out of this,” says Carla Rahn Phillips, a historian who has written a book about the San José. “The Spanish state, the Colombian government, the various indigenous groups, the treasure hunters. I don’t think there’s any way that everyone can be satisfied.”

The San José sank in 1708 as it sailed from what is now Panama towards the port city of Cartagena in Colombia. From there it was due to cross the Atlantic to Spain, but the Spanish were at war with the British at the time, and a British warship intercepted it.

The British wanted to seize the ship and its treasure, but fired a cannonball into the San José’s powder magazines by mistake. The ship blew up and sank within minutes.

The wreck lay on the seabed until the 1980s, when a US salvage company, Glocca Mora, said it had found it. It tried to persuade the Colombians to go into partnership to raise the treasure and split the proceeds, but the two sides could not agree on who should get what share, and plunged into a legal battle.

In 2015, the Colombians said they had found the ship, independently of the information provided by the Americans, on a different part of the sea bed. Since then they have argued that Glocca Mora, now known as Sea Search Armada, has no right to the ship or its treasure.

National Maritime Museum

National Maritime MuseumThe Spanish state has staked its claim, arguing that the San José and its cargo remains state property, and indigenous groups from Bolivia and Peru say they are entitled to at least a part of the booty.

They argue that it is not Spanish treasure because it was plundered by the Spanish from mines in the Andes during the colonial period.

“That wealth came from the mines of Potosí in the Bolivian highlands,” says Samuel Flores, a representative of the Qhara Qhara people, one of the indigenous groups.

“This cargo belongs to our people – the silver, the gold – and we think it should be raised from the sea bed to stop treasure hunters looting it. How many years have gone by? Three hundred years? They owe us that debt.”

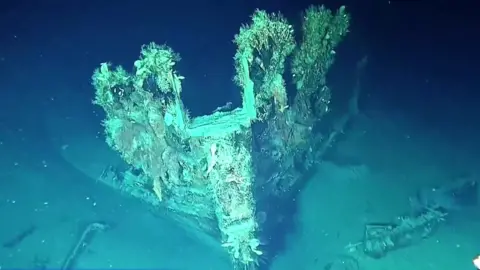

The Colombians have released tantalising videos of the San José, taken with submersible cameras. They show the prow of a wooden ship, encrusted with marine life, a few bronze cannons scattered across the sand, and blue-and-white porcelain and gold coins shining on the ocean floor.

As part of its court case at the Hague, Sea Search Armada commissioned a study of the cargo. It estimates its value at $7-18bn.

“This treasure that sank with the ship included seven million pesos, 116 steel chests full of emeralds, 30 million gold coins,” says Rahim Moloo, the lawyer representing Sea Search Armada. He described it as “the biggest treasure in the history of humanity”.

Others are less convinced.

Reuters

Reuters“I try to resist giving present-day estimates of anything,” says Ms Rahn Phillips.

“If you’re talking about gold and silver coins, do we make an estimate based on the weight of the gold now? Or do we look at what collectors might pay of these gold coins?

“To me it’s almost meaningless to try to come up with a number now. The estimates of the treasure hunters, to me, they’re laughable.”

While the San José is often described as the holy grail of shipwrecks, it is – according to the United Nations – just one of around three million sunken vessels on our ocean floors. There is often very little clarity over who owns them, who has the right to explore them, and – if there is treasure on board – who has the right to keep it.

In 1982, the United Nations adopted the Convention on the Law of the Sea – often described as “the constitution of the oceans”, but it says very little about shipwrecks. Because of that, the UN adopted a second set of rules in 2001 – the Unesco Underwater Cultural Heritage 2001 Convention.

That says far more about wrecks, but many countries have refused to ratify it, fearing it will weaken their claim to riches in their waters. Colombia and the US, for example, have not signed it.

“The legal framework right now is neither clear nor comprehensive,” says Michail Risvas, a lawyer at Southampton University in the UK. A specialist in international arbitration and maritime disputes, he adds: “I’m afraid international law does not have clear-cut answers.”

Rodrigo Pacheco Ruiz

Rodrigo Pacheco RuizFor many archaeologists, wrecks like the San José should be left in peace and explored “in situ” – on the ocean floor.

“If you just go down and take lots of artefacts and bring them to the surface, you just have a pile of stuff. There’s no story to tell,” says Rodrigo Pacheco Ruiz, a Mexican deep-sea diver who has explored dozens of wrecks around the world.

“You can just count coins, you can count porcelain, but there is no ‘why was this on board? Who was the owner? Where was it going?’ – the human story behind it.”

Juan Guillermo Martín, a Colombian maritime archaeologist who has followed the case of the San José closely, agrees.

“The treasure of the San José should remain at the bottom of the sea, along with the human remains of the 600 crew members who died there,” he says. “The treasure is part of the archaeological context, and as such has no commercial value. Its value is strictly scientific.”

[ad_2]

Source link