[ad_1]

BBC / Jon Parker Lee

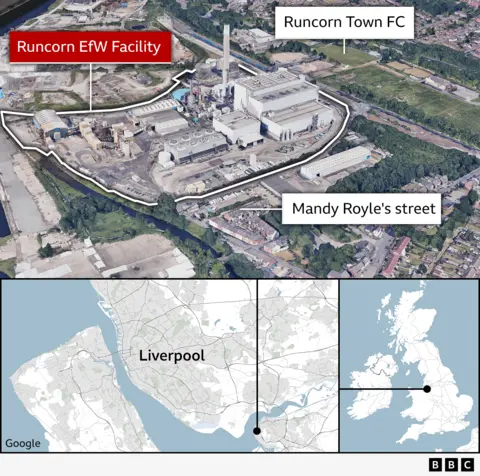

BBC / Jon Parker Lee“We have been inundated with flies, rats, smell, noise. It’s just been horrendous,” says Mandy Royle, who lives in the closest home to the UK’s biggest waste incinerator at Runcorn in Cheshire.

The facility generates electricity from burning nearly a million tonnes of household rubbish every year – but much of that waste doesn’t come from Ms Royle’s local area. Like many incinerators, deliveries come from hundreds of miles away.

BBC analysis suggests the burden of the UK’s waste is disproportionately falling on deprived areas such as Runcorn, which are 10 times more likely to have an energy-from-waste incinerator in their midst than in the wealthiest areas.

Many families nearby shared a £1m settlement after 180 of them launched a legal action over the pollution and disturbances from the Runcorn incinerator, the BBC can reveal.

But Ms Royle was one of a handful of people who did not sign the agreement, allowing her to speak out about life in the shadow of one of the UK’s giant waste plants.

“I’m just stuck in this little corner with a big monster staring at me and throwing what it does over me,” she says.

The others who took the cash, worth about £4,500 per family after legal costs, had to sign a strict non-disclosure agreement (NDA).

“Well, I think they’re being unfair in what they’re paying, and completely unfair in what they are doing,” says George Parker, who runs a local garage and also refused to sign the deal.

“It’s a million-pound hush fund and a gagging order. That’s why they’re doing it, they’re keeping everybody quiet.”

Viridor, which runs the Runcorn plant, said it would not comment on the settlement or on the non-disclosure agreement.

It said that noise and odour remained within permitted levels – regulated by the Environment Agency – and any complaints were fully investigated with feedback provided to residents.

Incinerators put in deprived areas

Energy-from-waste incinerators have boomed over the past decade as local councils have faced higher charges to bury rubbish in landfill sites.

This shift, though, has come at a big cost to the environment, with a BBC investigation showing that these plants now produce as much carbon per unit of energy than as if they were burning coal.

It also comes at a cost to those who live near them, say Ms Royle and Mr Parker.

“They put them in deprived areas, so people won’t complain because they know the majority of the people are in such a state they don’t know how to complain basically,” Mr Parker says.

Our investigation found breaches of air quality controls increased both at Runcorn and across incinerators in England between 2019 and 2023.

These controls restrict the levels of gases such as carbon dioxide that can be emitted.

The number of these permit breaches has risen from an average of 3.4 in 2019 to 5.5 per incinerator in 2023. Last year 73% of facilities in England reported transgressions.

Runcorn’s energy-from-waste site breached its permit 17 times in the past five years.

“The Runcorn Energy Recovery Facility (ERF) operates within a strict Environmental Permit and is heavily regulated by the Environment Agency, meaning it must comply with all the necessary regulations and permit conditions,” Viridor said in a statement.

“Should a permit limit be exceeded, a full and thorough investigation into the cause is carried out.”

Household waste is also being sent hundreds of miles across the country to be burned, or even sent abroad, BBC analysis of UK council data showed.

BBC / Jon Parker Lee

BBC / Jon Parker Lee In one of the worst examples, waste from Derby City Council and Derbyshire Council ended up at 19 different incinerators in one year – from Milton Keynes to North Yorkshire.

The increased movement of waste by train and lorry is producing even more carbon emissions and worsening local air pollution.

A spokesperson for Derby City Council and Derbyshire County Council said the councils had signed a new contract which will reduce this number to 13, and that “reducing waste miles is a key part of our strategy.”

In another case, County Durham sent 1,300 tonnes of waste last year to an undisclosed incinerator facility in Cyprus, even though there are incinerators nearby in north-west England. The council said it was “standard industry practice to divert waste from landfill through energy-from-waste facilities”.

‘The rubbish backyard of England’

While Runcorn is home to the UK’s biggest incinerator, a significant proportion of the town’s local rubbish is not burned at the site.

Instead, some of the waste from the borough of Halton, where Runcorn is located, and from other Merseyside towns, is sent by train about 150 miles across the country to the east coast, to be burned on Teesside.

This whole area along the River Tees has emerged as a UK hotspot for energy-from-waste. The region is now home to three active incinerators, with three more in various stages of planning.

“We have become a dumping ground for everybody else’s rubbish by stealth,” says a Liberal Democrat councillor in Redcar, Dr Tristan Learoyd.

He says that incinerators in the area are tied into long-term contracts with councils across the country, which he believes will see large amounts of carbon emitted every year for decades to come.

“There’s a potential here for the number of incinerators to be in double figures,” he says.

“For my hometown, which has suffered a massive decline over the years, it’s just another kick in the face. We’re becoming the rubbish backyard of England.”

Linda Martin lives on the nearest street to the Wilton 11 incinerator in Billingham, Teesside, which burns more than 400,000 tonnes of rubbish every year.

She questions whether people in the locality are seeing any direct economic benefit from the facility.

“This is our home and our area. Why should we have to put up with everything that we’re putting up with?” she says. “You know, we hear the noise constantly. We’ve got double glazing in, but it don’t work. You still hear the noise!”

For Eddie Thompson MBE, who runs a busy food bank in Runcorn, the psychological impact of locating large-scale incinerators in poor areas is very important.

“Mentally, people feel as though, in some cases, they are worthless. They have no sense of a future that they can see ahead of them.

“I don’t blame Viridor, but are we getting it right? Putting all the bad stuff in one place?”

[ad_2]

Source link