[ad_1]

BBC

BBCHow did one single social media post, taken down within hours for being false, still end up being viewed millions of times online and presented as credible evidence about the Southport attack?

The fatal stabbings at a children’s dance class on 29 July sparked riots in England and Northern Ireland. Unrest was fuelled by misinformation on social media that the suspect was an illegal migrant.

Responsibility for the violence that ensued cannot be sourced to a single person or post – but the BBC has previously established a clear pattern of social media influencers driving a message for people to gather for protests.

In the hours immediately after the Southport attack, several posts from a mixture of sources – including self-styled news accounts – began sharing false claims. This misinformation soon merged together.

By the time violence started in the Merseyside town on the evening of 30 July, some of the claims had been amplified or repeated by well-known online influencers such as Andrew Tate, who had millions of views repeating false narratives on X.

However, one LinkedIn post in particular – analysed by the BBC – appears to have had an outsized effect in stirring up the false belief that the dance class suspect was a migrant.

It was written by a local man, who could have had no idea of how far his words would travel.

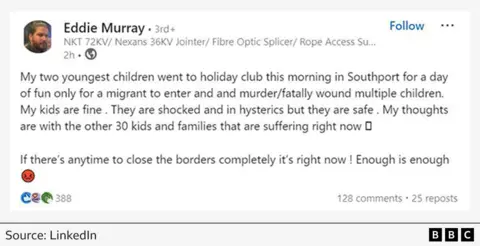

Eddie Murray – who lives near Southport – posted this message about three hours after the attack, stating that a migrant had carried it out:

“My two youngest children went to holiday club this morning in Southport for a day of fun only for a migrant to enter and murder/fatally wound multiple children. My kids are fine. They are shocked and in hysterics, but they are safe. My thoughts are with the other 30 kids and families that are suffering right now.

“If there’s any time to close the borders completely it’s right now! Enough is enough.”

The post implies that Mr Murray’s family were at the scene of the attack.

In fact, the BBC has been told that although they were in the neighbourhood, they had been turned away from the dance class because it was full.

Mr Murray’s post is one of the earliest examples of local testimony to incorrectly use the word “migrant”.

He later told us he was only posting the information he had been given.

What happened next demonstrates how an unsubstantiated claim can spread at speed, with no concern for whether it is true.

In the hours immediately after the stabbings, little information was released by Merseyside Police. It is normal for officers not to release information about a suspect under arrest – especially, as in this case, when they are under 18. Even in cases where the suspect has died, it can be many hours before they are named officially.

A short police statement was issued just after 13:00 to say that “armed police have detained a male and seized a knife”.

What followed was intense speculation – most of it on social media.

Mr Murray’s post was only seen by a few hundred people and it was later taken down. LinkedIn told us the post had been removed because it didn’t meet its policies on “harmful or false content”.

However, by then it had been copied and posted elsewhere and, within a few hours, had been viewed more than two million times on social media, according to BBC Verify analysis.

We found that on X, within an hour of the original post, a screenshot had been posted by an account calling for mass deportations. This would go on to have more than 130,000 views in total.

Next, at 16:23, an online news website based in India called Upuknews shared a retweet of Eddie Murray’s post, which it described as “confirmed”. This had more than half a million views.

By now, online speculation about the suspect was running high. There was a huge appetite to know what had happened in Southport.

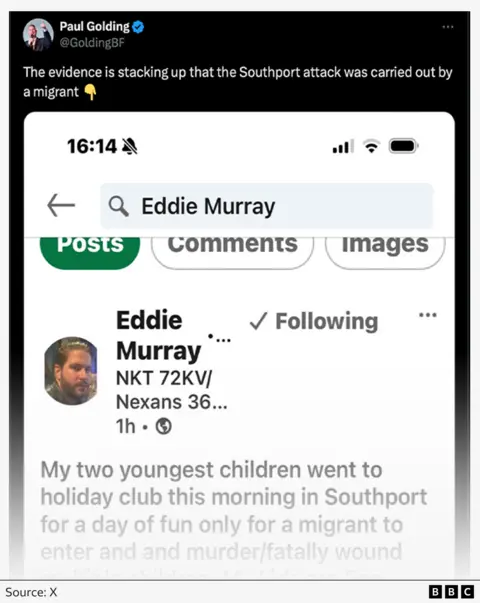

At the same time as Upuknews’s tweet, the Murray screenshot was posted on X by the co-leader of far-right group Britain First (and convicted criminal) Paul Golding. He claimed that the evidence was “stacking up that the Southport attack was carried out by a migrant”.

His post received nearly 110,000 views.

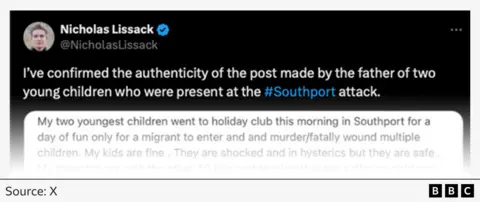

At 16:36, just 13 minutes later, Reform Party activist Nicholas Lissack tweeted he had “confirmed the authenticity of the post made by the father of the children who were present at the Southport Attack”.

Murray’s screenshot was also reposted by a white nationalist who wanted “the border closed” and made a call to “deport these savages”.

Many of these accounts are verified by X with purchased blue ticks, which means their posts have greater prominence on other users’ feeds.

Some of the accounts qualify for X monetisation and could receive direct payments from the platform.

Five hours after the attack, at 16:49, a false name for the suspect appeared on X alongside Eddie Murray’s screenshot, BBC analysis has found.

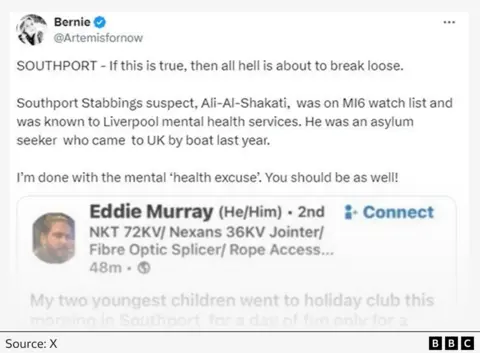

Bernie Spofforth, an account-holder once temporarily removed from X for allegedly posting misinformation about Covid, said the suspect had been named as “Ali-Al-Shakati”. In a statement the next day, Merseyside Police confirmed an incorrect name was being posted online for the suspect.

Ms Spofforth would later be arrested and released without charge. She has always denied any wrongdoing, insisting she only copied and pasted the information before deleting it and apologising. She told the BBC previously that she got the name from another post that has since been deleted.

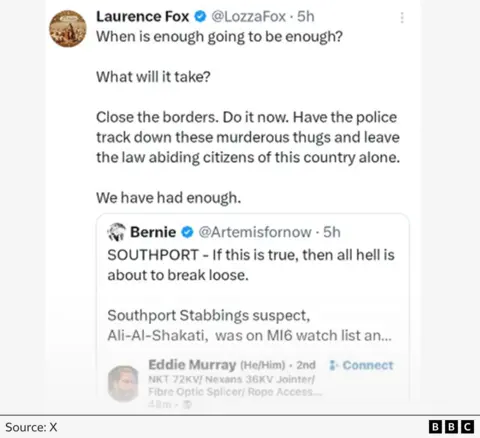

At 17:09, Laurence Fox, the actor and head of the right-wing Reclaim Party, reposted Ms Spofforth’s post alongside the Eddie Murray screenshot and wrote: “Close the borders.”

This single post was viewed 500,000 times.

In total, a screenshot of Eddie Murray’s original LinkedIn post was viewed more than three million times on X, according to BBC Verify analysis. However, it is clear he would have had no idea of how it would spread online.

We can also reveal more from Mr Murray’s other deleted LinkedIn posts, made on the day of the Southport attack.

This one repeats the Al-Shakati name:

“BBC news are lying. The Child murderer was from Africa. He was on MI6 watch. His name is Ali Al Shakati.”

Another reads:

“I see people stil [sic] believe what the left wing media say because it suits their own left wing woke agenda. It’s because of these sort of people the reason why this has happened in the first place.”

Mr Murray appeared to have become a credible source on social media for many. One woman on Facebook posted in support of him, asking others “You believe media/news over the people who was the witness…[?]”

Another person tweeted: “That post by Eddie Murray has been fact checked, it is on his LinkedIn and is true.”

We approached Mr Murray for a comment, first through LinkedIn, where he told us he didn’t regret his original post.

We later approached him in person. He said he had only posted what he had been told, genuinely believing his posts were correct.

When we asked Mr Murray why he had posted that the suspect’s name was Al-Shakati, he replied that he was just posting what others had been saying online.

At no point after 29 July did he correct any of his posts.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAt 17:25 the police said they had arrested a 17-year-old from Banks in Lancashire. Nearly two hours later, they clarified that he had been born in Cardiff.

But by this point, the relentless waves of misinformation were already propelling the town towards a riot, putting more lives at risk.

A key instigator was a group on the Telegram messaging app, set up about six hours after the stabbings. Called Southport Wake Up, the BBC has previously tracked down and confronted an administrator of the group. The account encouraged others to protest on St Luke’s Road at 20:00 on Tuesday 30 July, with online posters from the account also being shared on X, TikTok and Facebook.

That protest later turned into a riot. A BBC crew at the scene heard shouts of “You’re fake left-wing news”.

Misinformation was also amplified that evening by far-right activists for their own agendas. The BBC filmed David Miles, an activist for the white nationalist group Patriotic Alternative – one of the largest far-right movements in the UK. He was seen filming and talking to protesters near the police cordon for more than 30 minutes as officers were attacked and fires took hold.

Mr Miles also staged photos at the scene, wearing a “Free Sam Melia” T-shirt. Melia, a prominent regional organiser for Patriotic Alternative, was jailed earlier this year for inciting racial hatred. He was once in the neo-Nazi group National Action – since banned as a terrorist organisation.

Earlier that day, Mr Miles’s Telegram account shared a poster advertising the time and place for the protest. He later reposted dozens of locations for protests across the country.

As the riot took hold, a post on Mr Miles’s Telegram channel said, “what did they expect a garden party”.

When approached by the BBC, Mr Miles denied exploiting the deaths of children. He said he wasn’t violent and described the riots as “awful”.

In response to the Southport stabbings, and the lack of information given by police about the suspect in the face of false claims, the government’s independent reviewer of terrorism legislation, Jonathan Hall KC, said that the law, as it currently stands, “stokes the risk of online disinformation” (the deliberate spreading of false information).

He also stated the false claims that circulated on social media about the identity and asylum status of the suspect were “plausibly connected to some of the violence that followed”.

Mr Hall has written to the Law Commission suggesting legal reforms which would allow names, nationality, and ages of individuals to be reported where there is no substantial risk of prejudice.

Many of the misleading posts we have analysed are still on X and Facebook, and David Miles is still posting on Telegram.

The government asked Ofcom to consider how illegal content, particularly disinformation, spread during the unrest.

The media regulator concluded that there was a “clear connection” between the violent disorder in England and Northern Ireland in the summer and posts on social media and messaging apps.

In an open letter setting out its findings, Ofcom boss Dame Melanie Dawes said such content spread “widely and quickly” online following the stabbings in Southport.

Meanwhile, the government has told the BBC it is working at pace to implement the Online Safety Act, which requires social media platforms to remove illegal content and prevent the deliberate spread of false information.

The act was passed into law in October 2023, but its protections have yet to come into effect.

We approached X for a comment, but have not received a reply.

Additional reporting by Rebecca Wearn, Phill Edwards & Daniel de Simone

[ad_2]

Source link freeslots dinogame telegram营销