[ad_1]

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAfter 10 weeks, the mass rape trial that has shocked France is moving on to the final phase of closing statements.

The case focuses on a formerly married couple, Dominique and Gisèle Pelicot, pensioners who are now in their early 70s.

Ms Pelicot’s legal team will give their final statements on Tuesday, and the defence will then follow, ahead of a verdict from a panel of five judges expected on 20 December.

Dominique Pelicot went on trial with 50 other men in the southern city of Avignon in September.

Every chapter of this case has played out in the full glare of publicity because Ms Pelicot has waived her anonymity, making the whole trial open to the media and the public.

In France, it has become known as the Affaire Mazan, after the village near Avignon where the Pelicots lived.

In November 2020, Dominique Pelicot admitted drugging his then-wife for almost a decade and recruiting dozens of men online to rape her in their home when she was unconscious.

Police tracked down his co-accused from thousands of videos they found on Mr Pelicot’s laptop, although they were unable to identify an additional 21 men. Investigators said they have evidence of around 200 rapes carried out between 2011 and 2020.

The majority of the defendants deny the charges of rape, arguing that they cannot be guilty because they did not realise Ms Pelicot was unconscious and therefore did not “know” they were raping her.

That line of defence has sparked a nationwide discussion on whether consent should be added to France’s legal definition of rape, currently defined as “any act of sexual penetration committed against another person by violence, constraint, threat or surprise”.

The trial has also shone a light on the issue of chemical submission – drug-induced sexual assault.

Blackouts and memory loss after years of marriage

Dominique and Gisèle Pelicot, who were both born in 1952, married in 1973 and had three children. She worked as a manager in a large French company, while he – a trained electrician – started several ultimately unsuccessful businesses.

The Pelicots lived in the Paris region until 2013, when they retired to the picturesque southern village of Mazan. They had a big house with a swimming pool and often used to entertain their extended family during the summer holidays.

By all accounts, they were a happy, close-knit couple. “We shared holidays, anniversaries, Christmases… All of that, for me, was happiness,” Ms Pelicot has said.

Between 2011 and 2020, Ms Pelicot experienced unsettling symptoms she took to be signs of Alzheimer’s or a brain tumour, and underwent extensive medical exams. The blackouts and memory loss were, in fact, side-effects of the drugs her husband was giving her without her knowledge.

Ms Pelicot divorced her husband soon after his crimes came to light. She is only using her married name for the purposes of the trial.

Dominique Pelicot has been in jail since November 2020. He will be sentenced next month, alongside the other 50 defendants.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHow the case came to light

In September 2020, Dominique Pelicot was spotted filming under women’s skirts by a security guard in a supermarket in southern France.

Police detained him and confiscated his electronic devices. They noticed suspicious chats on his Skype account, then found thousands of videos of men having sex with a seemingly unconscious woman – Mr Pelicot’s wife, Gisèle.

Investigators worked for weeks to gather enough evidence to take Mr Pelicot into custody and eventually arrested him in November 2020. He immediately admitted all the charges.

When Ms Pelicot was questioned by police and shown photos and videos in which she appeared unconscious, it became clear she had no knowledge of what had happened to her. She denied ever giving her consent to having sex with other men and realised her husband had drugged her for almost a decade.

Fifty-one men in the dock

Fifty men – aged between 26 and 72 years old – are on trial alongside Mr Pelicot.

They hail from all walks of life: among them are a fireman, a carpenter, a nurse and a journalist. Many are married with children. Most lived within a 60km (37 miles) distance of the Pelicots’ residence.

A handful have admitted to raping Ms Pelicot.

The majority, however, reject the charges. Their defence hinges on the fact they did not believe what they were doing was rape, because they were not aware that she was unconscious and therefore could not give her consent.

Mr Pelicot has repeatedly denied this was the case, insisting that when he recruited men on the internet he made it abundantly clear that his wife would be asleep. “They all knew, they cannot say the contrary,” he has said.

What Gisèle Pelicot has told the court so far

It was Gisèle Pelicot who decided to waive her anonymity – highly unusual in cases of rape. Her legal team also insisted for the videos of the alleged rapes to be shown in court.

Ms Pelicot has said that she hopes her decision will empower other survivors of sexual violence to speak out: “I want all women who have been raped to say: Madame Pelicot did it, I can too. I don’t want them to be ashamed any longer.”

She has forcefully hit back at “humiliating” suggestions by the defence that she may have been drunk or pretending to be asleep during the alleged rapes, stating that she was never interested in partner-swapping or threesomes.

Ms Pelicot has also, however, spoken candidly about the devastation that her husband’s abuse and lies have wreaked on her life. “People may see me and think: that woman is strong,” she said. “The facade may be solid, but behind it lies a field of ruins.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHow France has responded to the trial

The horror of Dominique Pelicot’s actions, the sheer number of men implicated in the case and Gisèle Pelicot’s decision to push for an open trial has meant that the proceedings have garnered significant attention.

Dozens of members of the public attend court in Avignon each day to back Ms Pelicot, meeting her with applause and handing her flowers.

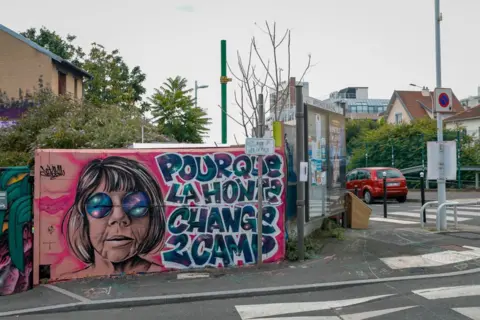

Murals have appeared across the country depicting her distinctive look of a short bob and round sunglasses, and demonstrations have taken place all over France in her support.

Above all, she is credited by many with sparking a conversation on rape culture, misogyny and chemical submission.

Several feminist groups are now pushing for the government to amend its definition of rape to include consent, as is already the case in many European countries.

“Society has already accepted the fact that the difference between sex and rape is consent,” said Greens senator Mélanie Vogel, who proposed a consent-based rape law last year. “Criminal law, however, has not.”

[ad_2]

Source link