[ad_1]

BBC

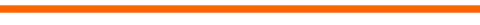

BBCOn a spring day, Hamid Khoshsiar decided to make the perilous journey into the European Union. He was 31 at the time, an Iranian refugee who had been living in Turkey for two years. But in 2019, he felt it was time to go.

Starting out in Igneada, in the north of the country, he walked along a slippery, uneven trail for half a day, through dense forest and sharp shrubbery in the direction of Bulgaria. Eventually he reached the border.

His best option, he decided, was to swim across a small river. The waters were mercifully calm. Packing his scant belongings into plastic bags, he waded in.

“There was so much adrenaline in my blood,” he remembers. “The only thing that was important to me was safety. All my mind was about that: am I going to find safety or not?”

It would take him 20 hours to reach safety in Bulgaria, where he now lives with refugee status. As for the journey, he says he could have died from dehydration had he not been found by a police patrol. Still, it was the best decision of his life.

“It was worth it because I didn’t have any other option. I was so lucky.”

Over the past five years, more and more migrants have decided to try their luck following the same path, known as the Eastern Mediterranean route. It starts in Turkey and moves into either Bulgaria or Greece; and then, for many, deeper in Europe.

Whilst other routes – like the path from the north African coast to Italy – have seen a fall, the numbers entering Europe via this Eastern Mediterranean route tripled between 2021 and 2023 and is still rising, according to EU border agency Frontex.

It now stands at well over 60,000 a year. Many are Afghan and a number are Turkish and Syrian. Some, eventually, end up on the shores of Britain.

Since taking power, the Labour government has repeatedly promised to “smash” the smuggling gangs who lead them here.

Sir Keir Starmer’s strategy focuses heavily on policing. He has promised to treat smugglers like terrorists, disrupting their plans “before they act”. On 4 November, the prime minister announced plans to create a new Border Security Command, which the government say will have enhanced powers to trace suspected traffickers and shut down their bank accounts. One hundred additional specialist investigators will be assigned to the National Crime Agency (NCA), one of the UK bodies tasked with cracking down on people smugglers, while the Crown Prosecution Service will deliver charging decisions more quickly in international organised crime cases.

But is it enough? After all, the Conservatives had their own version of Labour’s slogan, promising to “stop the boats” – and yet in the year to June 2024, some 38,784 irregular arrivals were detected – 81% of them arrived in small boats.

So what makes Labour think it will fare differently, and that its police-first strategy will work?

Over the last week, as part of a series on BBC Radio 4’s Today programme, we traced the path of migrants from Turkey to Bulgaria to the rest of Europe – the “biggest growth route” for those travelling into Europe, according to the University of Oxford’s Migration Observatory – in search of what it will really take to “smash the gangs”.

When we talk about smuggling gangs, we tend to focus on the end of the process, such as the UK’s relations with France, and on the movement of people across the English Channel, but our route marks the start of the journey: it’s where migrants first enter Europe.

Along the way, we spoke to migrants who shared their complicated reasons for putting their lives in the hands of people smugglers. What soon became clear was the sheer magnitude of the government’s task.

Gateway to Europe: the Turkey challenge

The crowded shopping bazaar in the Istanbul district of Esenyurt is popular with the thousands of Syrian refugees who live in the region. “You can see Syrian shops here,” Husam, a Syrian refugee, told us as he showed us around after Friday prayers. “Many were not here in 2015. You have falafel, shawarma – many shops for Syrian food. It was a comfortable, safe place for Syrians.” But now the mood is darkening.

“In the past few years it’s not safe any more,” he explains. “There are groups of racist people who don’t like refugees. On public transportation you cannot speak comfortably in Arabic on your phone. People are attacked [for] speaking Arabic.”

Turkey has more refugees than any other country. It opened its borders to people fleeing the war in Syria in 2011; now there are upwards of three million Syrian refugees in Turkey, according to the UN. But Turks are getting restless. President Recep Erdogan has urged refugees – who he calls “guests” – to go home.

Migrants without papers are being arrested and deported. Even those who have papers face being harassed, and now many who made temporary homes in Turkey want to leave – legally if possible – but, where necessary, they use people smugglers.

All of this is being watched by Westminster. With so many people so desperate to move westwards, one of the British Government’s prime tasks, if it is to keep its promise to reduce illegal arrivals, is to start cracking Turkey’s people-smuggling model. And that starts with social media.

For years, smugglers have used Facebook and other platforms to advertise safe passage between countries, often including prices and package deals such as “kids go free”.

Over a traditional Syrian meat-and-rice dish of maqluba, Ali, a former footballer from Damascus, gets out his phone and shows us social media videos that promote smuggling routes. They are slick and professional, with pictures of boats and people looking joyous as they arrive in Greece.

“Absolutely I’m thinking about leaving,” Ali admits. “Not just me, all my friends.”

Britain is one of the destinations he has in mind, along with the Netherlands and Germany.

Stemming the flow from Turkey

The exodus from Turkey is not surprising, says Marc Pierini, EU ambassador to Turkey between 2006 and 2011. “Syrian refugees in Turkey have over the past few years become the scapegoat… A whole xenophobic narrative has been [created] by the authorities.”

Turkey’s poor economy is only adding to the problem, argues Murat Erdoğan, a professor of migration studies at Ankara University, who is no relation to the president. Interest rates were raised to 40% last year amid soaring inflation.

For years, successive European governments have attempted to crack down on the smuggling ring here by giving money and logistical support to Turkish police and coastguard. A 2016 deal between the EU and Turkey – in which Turkey was given aid in return for its help reducing the flow of migrants travelling to Greece on boats – was an early attempt to undermine the smuggling business model.

But Rob Jones, director of operations at the NCA, says cracking down on the trade is complex – and even more difficult than policing the movement of illegal drugs. “It’s harder, it’s different, it’s more organic,” he says. “It relies on a series of informal trusted relationships”.

Smuggling gangs often use hawala – a payment method that avoids formal banking and instead relies on a network of agents to deliver cash across borders. “That means we don’t have large amounts of cash moving between borders or even electronically, like we do with the drug trade,” he says. “It’s also difficult because it utilises ubiquitous social media apps which allow people to be handed between groups at ease. “

In Britain, ministers of successive governments have recognised this as part of the problem, as well as the need to tackle social media advertising. Since 2021, the NCA has worked with Meta, X, TikTok and YouTube to remove posts promoting smuggling services. By this summer, 12,000 posts had been deleted, the agency said.

The newly appointed Border Security Commander, Martin Hewitt, has told us: “We will keep chipping away and undermining their business to the point where that is no longer viable and profitable.”

But our experience in Turkey showed us that – to date – it’s still possible to connect with a smuggler at the click of a button.

Crackdown at the border

The NCA has highlighted a particular area that is a “crucible” for organised immigration crime: the crossing between Turkey and Bulgaria, which marks the EU’s external frontier.

We visited the tiny Bulgarian mountain village of Shtit, a sleepy place with dirt roads and rusting farm machinery – a place that doesn’t seem to hold much geopolitical significance, but that’s right at the border, which is marked by a 4m high fence and razor wire.

“It’s very sharp and it’s almost impossible to climb with bare hands,” says Hamid, the Iranian refugee who crossed it in 2019. “Usually they’re using ladders, but there’s some places [along the fence] that they’ve already cut.”

Our conversation is interrupted by a passing patrol car. Two uniformed officers warn us not to take photographs of the border; presumably, if shared on social media they can help migrants make the crossing.

Nikolai, a chef in a local restaurant, tells us he has seen a marked increase in security in the area – many of the guards are from Germany and Poland, and are working in Bulgaria as part of the EU’s border force, Frontex.

Certainly, the Bulgarians have made strides in policing their side of the border. In recent years they have installed cameras, drones, and ramped up the number of security staff.

This ring-of-steel-style system has had some success: the number of migrants crossing here has fallen in the last two years, says Atanas Rusev, director of the Security Programme at the Centre for Study of Democracy. But there are gaps.

The porousness of the border is apparent about 32km down the road, at the Kapitan Andreevo crossing, uniting Greece, Bulgaria, and Turkey – the busiest such border in Europe. The terrain is mountainous, with parts covered by thick forests making it easy for migrants to go undetected.

“In order to police you need thousands of people on the ground,” Mr Rusev explains. “You cannot put a man every five metres – so you have these patrols that are moving across certain sections of the border. Then you have the fence, but the fence is not a big obstacle because you need a simple wooden ladder.”

The smuggling gangs are clever and “know the terrain very well”, he explains. “If you think that you can stop these irregular flows just with policing and prosecution and securitising, it’s a road to nowhere.”

Fines for carrying inflatable boats

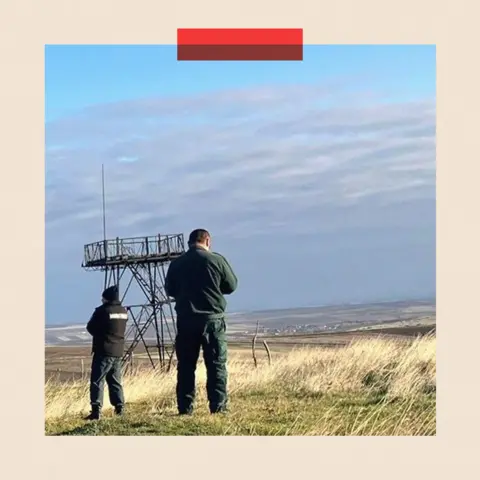

And they’re not just trying to stop people. Many of the rubber inflatable boats used to smuggle migrants across the Channel are manufactured in Turkey and transported over this very border.

One difficulty stopping the boats is that it is legal to carry inflatables across Europe; they might be used for a fishing trip. But following talks with the UK, the Bulgarians have changed their customs regulations to say that only certain Turkish companies are licensed to export boats.

Anyone found with an unlicensed vessel in the back of their car can face a €2,000 (£1,666) euro fine. To help detect those boats is a dog, Adele, trained by the UK’s National Crime Agency to sniff out rubber. Her harness carries both Bulgarian and UK flags.

I point out to Valerie, the border agent showing us around, that smuggling gangs can make thousands of pounds of profit off each passenger. Perhaps the gangs are happy to risk a €2,000 fine?

“Maybe,” comes the answer, “but we stop some.”

So where does this leave Britain?

Back in Britain, the prime minister has suggested that policing, intelligence and more international cooperation is the answer. Our experience in Bulgaria of the attempt to disrupt the trade in boats being exported from Turkey highlights the benefits of this approach and also its limitations. Even with drones, cameras and security staff, thousands of people stream into the country illegally every year. It’s certainly not a promising sign.

And yet the government’s heavy focus on policing and security has paid off in some ways. Earlier this month, Amanj Hasan Zada, who organised cross-Channel smuggling from his home in Lancashire and was feted as “the best smuggler”, was convicted and given a 17-year sentence.

Peter Walsh, head of the Migration Observatory, is more optimistic than some about Labour’s beefed-up security approach, pointing out that it’s possible to reduce the flow of people. But he stresses that the success or failure ultimately depends on global trends in people smuggling, over which UK ministers have little control.

He also fears police might end up in a game of whack-a-mole. “The people most directly involved in smuggling activity can [be] apprehended – but they can quickly be replaced.”

Which poses a new question. As he puts it: can you apprehend people more quickly than they can be replaced?

Alternative routes

There are alternative strategies to police-first – but each is loaded with its own problems. For example, by giving money to countries such as Syria, it’s possible to tackle what are termed the “root causes” of migration so there’s less need for refugees to flee. The prime minister made a gesture to this strategy in the summer, pledging £84m for education and employment opportunities in Africa and Middle East. But even the most optimistic of humanitarians don’t think this is a solution in the short- or even medium-term, or that £84m is enough to fix the problems.

Then there’s the prospect of bilateral deals. The “gold standard” for the UK would be to strike a generous beach-returns deal with France, says Mr Walsh, in which France agrees to take back migrants who arrive via the Channel and intercept boats. “But what’s in it for France?” Mr Walsh asks.

Finally there’s the option of offering “safe and legal” routes for refugees to enter Britain, the policy preferred by some charities. But other experts suggest this would amount only to a few thousand people per year – and attempt to seriously ramp up numbers may become politically toxic.

“There’s always going to be more people that want to arrive than can arrive,“ added Mr Walsh. And those people will make it through any means necessary.

Of everything we saw in Turkey and Bulgaria, one memory stays with me that proves this very point. It was at the Harmanli refugee camp, the largest in Bulgaria. There, we met a group of 10 Syrian men who had recently made the crossing from Turkey. Their smugglers knew exactly where they could climb over the fence, they told us.

But what about the hi-tech cameras, the drones, and the extra police, I asked? They just shrugged. It didn’t seem like they’d struggled.

It impressed upon me the enormity of Labour’s task. After all, ministers can throw whatever resources they want at the issue of gangs but if migrants are determined enough, and if the money for gangsters is tempting enough, some will always find a way through.

Mr Walsh is also sceptical of whether people smuggling gangs can be cracked at scale, drawing the comparison of drugs gangs. ”There’s a fair amount of investment that goes into controlling the sale of illicit drugs, yet they continue,” he argues. “So the idea that you can stamp it out entirely is just not feasible.

“Yes you can make a difference, but it’s impossible to reduce it to zero.”

No-one who works with migrants, no-one who works on border security, would ever say the sort of words or phrases routinely in political slogans: “stop the boats” or “smash the gangs”. What they talk about instead is a much more modest ambition of making it harder to cross borders without the right paperwork, reducing the number who do so and disrupting the people smugglers. But they all accept that those who really want to make it from one side of the border to the other will probably eventually succeed.

BBC InDepth is the new home on the website and app for the best analysis and expertise from our top journalists. Under a distinctive new brand, we’ll bring you fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions, and deep reporting on the biggest issues to help you make sense of a complex world. And we’ll be showcasing thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. We’re starting small but thinking big, and we want to know what you think – you can send us your feedback by clicking on the button below.

[ad_2]

Source link